Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

How To Build A Superintelligence | Highlights from S2EP2

Vinay Gupta on AI’s Impact on Jobs and Society | Mindplex Podcast – S2EP2

Fat Finger Friends: Miner Morality in the New Money System

We all make mistakes. A misclick here, a fat finger there – suddenly your new shoes are being delivered to your ex’s address and you just gave your nephew $200 instead of $20 for Christmas. Are you going to tell him he needs to give $180 back?

When dealing with TradFi (‘traditional finance’) apps like Revolut, mistakes are made with money. Some are more serious than others. Gridlocked bureaucracies can take their time giving you your money back. Others may never give it back at all.

There is recourse, though. Your bank offers you protection and, if they don’t, the law can be on your side. The state effectively rests upon enforcing the fiat ledger (if you don’t pay your bills you go to prison), so there are safeguards for when you mess up.

No Takesies-Backsies

In crypto, not so much. In fact, not at all. The beauty of crypto, the very reason it has any value at all, is its ability to administer a money system at a far greater efficiency than all the banks, lawyers, police, accountants and more that make up our current monetary system. As a result, you can send large sums of money cheaply, and small sums directly and instantly, with near-zero friction. However, unlike TradFi, you cannot make mistakes.

If you send 1 BTC to someone instead of 0.1 – that’s it. It can’t be reversed by the blockchain. There is no system for getting your money back. All blocks are final – that’s the point. It’s an immutable record of accounting. The only way to correct the mistake is to ask nicely and hope the person sends it back. Otherwise there is nothing you can do, and no one who can help you. So, either you start polishing your wrench, or you move on. And if you sent it to the wrong address, even that won’t save you. The money is gone forever – burned in a cryptographic pyre.

That’s not the only mistake you can make. When sending crypto transactions, you must pay gas. Gas is the fee paid to the miners of a given protocol for maintaining the decentralised ledger. This fee is variable; it changes depending on how busy the network is, and the demand for block space. It’s also editable. If you, a user, want to put your BTC transaction at the top of the pile and be included in the next block, you can tip the miner to speed up your transaction.

Fat Fingers, Fatter Mistakes

Do you see where this is going? This time those fat fingers drop a bigger bag. When dealing with bitcoin (worth, at time of writing, $42,000), an extra zero can mean a lot of money. As we said, there is no recourse. Add in bad (or unfamiliar) UX and it’s a fertile ground for mistakes to be made. All tips paid are final, according at least to the protocol.

Except not quite. Miners do need to accept the transaction and, as such, can choose not to. One user who paid a record $3 million dollar tip to Antpool, was relieved when Antpool said that they had spotted the absurd tip, and said that they would refund it provided the sending address could provide proof. It’s not the first time such a large amount has been paid, even by institutions where safe management is key to their reputation. In one case, Paxos overpaid $500,000 to a miner through simple mechanical and interface error. That miner agreed, too, to refund it. But not without expressing frustrations, and asking the community whether he should repay it in the first place. The community voted to just give it to other Bitcoin users. If it was an individual and not a perceived ‘institution’, perhaps this sentiment would be different.

The Problem with ‘Miner Morality’

Yet the issue remains. Miners are focused on upkeep and collection of payments. They don’t want to be moral arbiters of how much is too much, of what is or isn’t a mistake. They just want to collect the fees. Asking miners to be responsible for fat finger errors puts them in a confusing position. What is their exact job-description then? They are simply committed to upholding the ledger, and earning their due for doing so. They don’t want to become institutions, or be on the moral hook for funds sent to them in error – it somewhat defeats the point of peer-to-peer currencies. How would the institutions work? Tesla gets its mistakes remedied but John Doe doesn’t? That seems worse than the current system.

However, Antpool’s fast, commendable response, replete with a ‘risk control system’ and clear deadlines and protocols for repayment is more agreeable in a world where institutions start issuing Bitcoin ETFs. Perhaps that’s what we want, but perhaps it also betrays a truth about what Bitcoin mining is becoming. Miner pools are becoming ever more powerful, controlling more of the hash rate. If a powerful, centralised cartel of mega-miners are responsible for most of the network’s hashrate, it creates problems – especially as huge mainstream institutions fund their pensions with Bitcoin instruments packaged by Wall Street.

Own Your Mistakes

Adoption is coming, but fat fingers will remain. Blockchain’s genius resides in non-permissioned ledgers, where your money is in your hands and your fumbles are your own. It’s worth the price of admission to have the speed, sanctity and security that blockchains offer. Miners should not be compelled to refund fat fingers, even if it’s commendable that they do, and we should not drag them into a faux-corporate architecture that threatens to diminish why we love the ledger in the first place.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Building Refugee Countries to Save Lives | Highlights from S2EP2

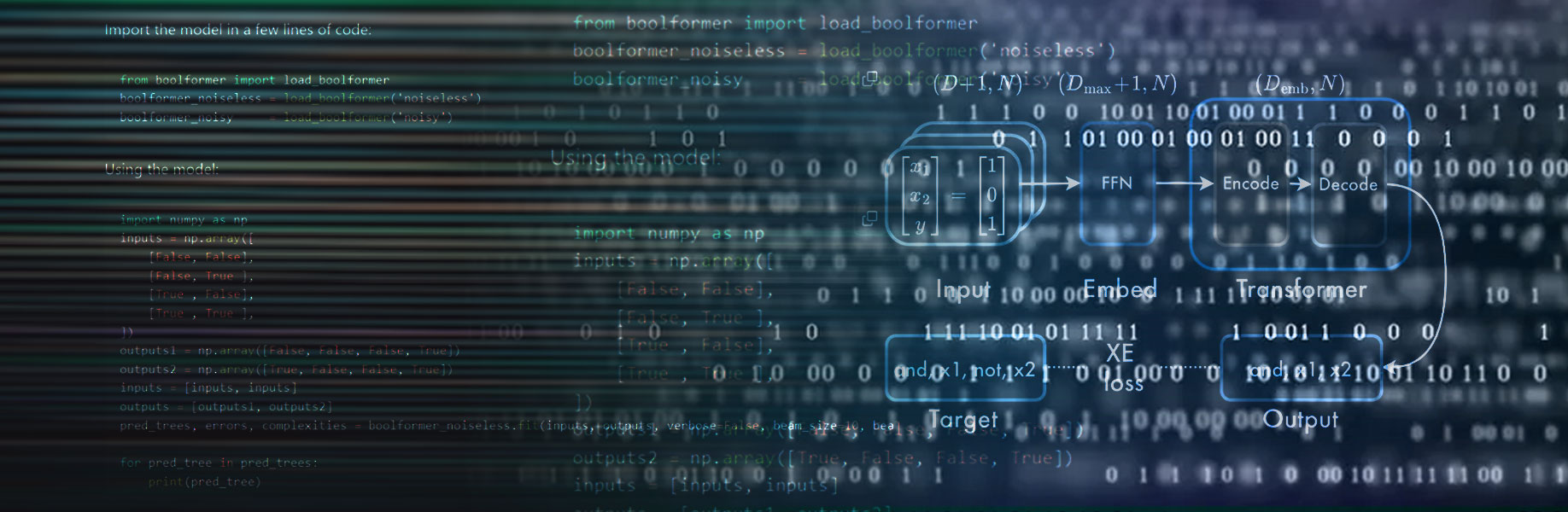

Boolformer: The First Transformer Architecture Trained to Perform End-to-End Symbolic Regression of Boolean Functions

One of the many domains where deep neural networks, particularly the Transformer types, are anticipated to achieve their next breakthrough is in the realm of scientific exploration. This is due to their demonstrated proficiency in areas such as computer vision and language modeling, where they have already demonstrated notable success. However, these neural networks seem to be limited in their ability to perform logic tasks. These tasks, which could range from traditional vision or language tasks whose input has a combinatorial nature, seem to make representative data sampling challenging. This has motivated the machine learning community to heavily focus on reasoning tasks, including explicit tasks in the logical domain (like arithmetic and algebra, algorithmic CLRS or LEGO), or implicit reasoning in other modes (such as Pointer Value Retrieval or Clevr for vision models, LogiQA and GSM8K for language models).

Since these efforts continue to be difficult for Standard Transformer Structures, it is only natural to investigate whether they may be managed more efficiently with alternative methods, such as making better use of the Boolean nature of the task. In this regard, the process of Training transformers leads to an undesirable generalization, and this in turn makes interpretability challenging. This raises the question of how to improve generalization and interoperability of these Transformer models. But research by a team from Apple and EPFL seems to have found a breakthrough which can answer that question. They have come up with the Boolformer, the first neural network of the Transformer design to solve problems in symbolic logic. The Boolformer can predict compactcompcat formulas for complex functions which were not seen during training, thus generalizing consistently to functions and data that are more sophisticated than those during the training.

The boolformer predicts Boolean formula, which can be seen as a symbolic expression of the 3 basic logic gates: AND, OR and NOT. The model is trained with a set of training examples, which are synthetically created functions. The truth table of the functions acts as input and their formula used as targets. This setup, with control of the data generation process helps with gaining both generalization and interpretability. The researchers from Apple and EFPL have demonstrated the powerful performance of this approach in both theoretical and real world settings, and they also lay the foundation for future advancements in this area.

The research by the team has made several contributions. By training transformers over synthetic datasets to perform end-to-end symbolic regression of boolean regression, researchers show that the Boolformer can predict a compact formula when given a full truth table of unseen function. The researchers also demonstrate that the Boolformer can handle noisy and incomplete data, by giving as inputs truth tables with flipped bits and irrelevant variables. Not only this, but they have evaluated the Boolformer with various real-world binary classification tasks from the PMLB database, and show that it is competitive with classic machine learning approaches like Random Forests while providing interpretable predictions. They have also applied the Model on the well-studied task of modeling gene-regulatory networks (GRNs) in biology. They demonstrate that the Boolformer is competitive with current state-of-the-art approaches, and that it even has inference time that is several times faster than the other methods.

Their code and models are open source and available to the public, which can be found on their github. They have made sure that anyone who wants to contribute to their work is easily set-up and starts work. Do check their work.

There seem to be some constraints that point to new areas for research however. First, the quadratic cost of self-attention limits the model’s effectiveness on high-dimensional functions and big datasets, which caps the number of input points at one thousand. Second, because the logical functions of the training sets did not include the XOR gate explicitly, the model has been limited in the compactness of the formulas it predicts and in its ability to express complex formulas such as parity functions. This limitation came due to the simplification process used during the generation procedure. The process required rewriting the XOR gate in terms of AND, OR and NOT. Adapting the production of simplified formulas consisting of XOR gates as well as operators with higher parity is left as a future effort by the research team. And thirdly the formulas predicted by the model are only single-output functions and gates with a fan-out of one (Multi output functions are predicted independently component-wise).

In conclusion, The Boolformer is a new breakthrough in the field of Machine Learning, which helps in the advancement of the field, making machine learning more accessible, efficient and performative, as well as unlocking the potential of AI in newer domains and in the process helping the advancement of science and knowledge.

Do not forget to check out the paper and their github.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Transforming Industrial Panels into Affordable Housing | Highlights from S2EP2

Sanitation Danger at Burning Man | Highlights from S2EP2

Breaking Ground in 3D Modeling: Unveiling 3D-GPT

Researchers from the Australian National University, University of Oxford, and Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence have collaboratively developed a groundbreaking framework known as 3D-GPT for instruction-driven 3D modeling.

The framework leverages large language models (LLMs) to dissect procedural 3D modeling tasks into manageable segments and appoints the appropriate agent for each task.

The paper begins by highlighting the increasing use of generative AI systems in various fields such as medicine, news, politics, and social interaction. These systems are becoming more widespread and are used to create content across different formats. However, as these technologies become more prevalent and integrated into various applications, concerns arise regarding public safety. Consequently, evaluating the potential risks posed by generative AI systems is becoming a priority for AI developers, policymakers, regulators, and civil society.

To address this issue, the researchers introduce 3D-GPT, a framework that utilizes large language models (LLMs) for instruction-driven 3D modeling. The framework positions LLMs as proficient problem solvers that can break down the procedural 3D modeling tasks into accessible segments and appoint the apt agent for each task.

The 3D-GPT framework integrates three core agents: the task dispatch agent, the conceptualization agent, and the modeling agent. They work together to achieve two main objectives. First, they enhance initial scene descriptions by evolving them into detailed forms while dynamically adapting the text based on subsequent instructions. Second, they integrate procedural generation by extracting parameter values from enriched text to effortlessly interface with 3D software for asset creation.

The task dispatch agent plays a crucial role in identifying the required functions for each instructional input. For instance, when presented with an instruction such as “translate the scene into a winter setting”, it pinpoints functions like add snow layer() and update trees(). This pivotal role played by the task dispatch agent is instrumental in facilitating efficient task coordination between the conceptualization and modeling agents. From a safety perspective, the task dispatch agent ensures that only appropriate and safe functions are selected for execution, thereby mitigating potential risks associated with the deployment of generative AI systems.

The conceptualization agent enriches the user-provided text description into detailed appearance descriptions. After the task dispatch agent selects the required functions, we send the user input text and the corresponding function-specific information to the conceptualization agent and request augmented text. In terms of safety, the conceptualization agent plays a vital role in ensuring that the enriched text descriptions accurately represent the user’s instructions, thereby preventing potential misinterpretations or misuse of the 3D modeling functions.

The modeling agent deduces the parameters for each selected function and generates Python code scripts to invoke Blender’s API. The generated Python code script interfaces with Blender’s API for 3D content creation and rendering. Regarding safety, the modeling agent ensures that the inferred parameters and the generated Python code scripts are safe and appropriate for the selected functions. This process helps to avoid potential safety issues that could arise from incorrect parameter values or inappropriate function calls.

The researchers conducted several experiments to showcase the proficiency of 3D-GPT in consistently generating results that align with user instructions. They also conducted an ablation study to systematically examine the contributions of each agent within their multi-agent system.

Despite its promising results, the framework has several limitations. These include limited curve control and shading design, dependence on procedural generation algorithms, and challenges in processing multi-modal instructions. Future research directions include LLM 3D fine-tuning, autonomous rule discovery, and multi-modal instruction processing.

In summary, the research paper introduces a novel framework that holds promise in enhancing human-AI communication in the context of 3D design and delivering high-quality results.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)