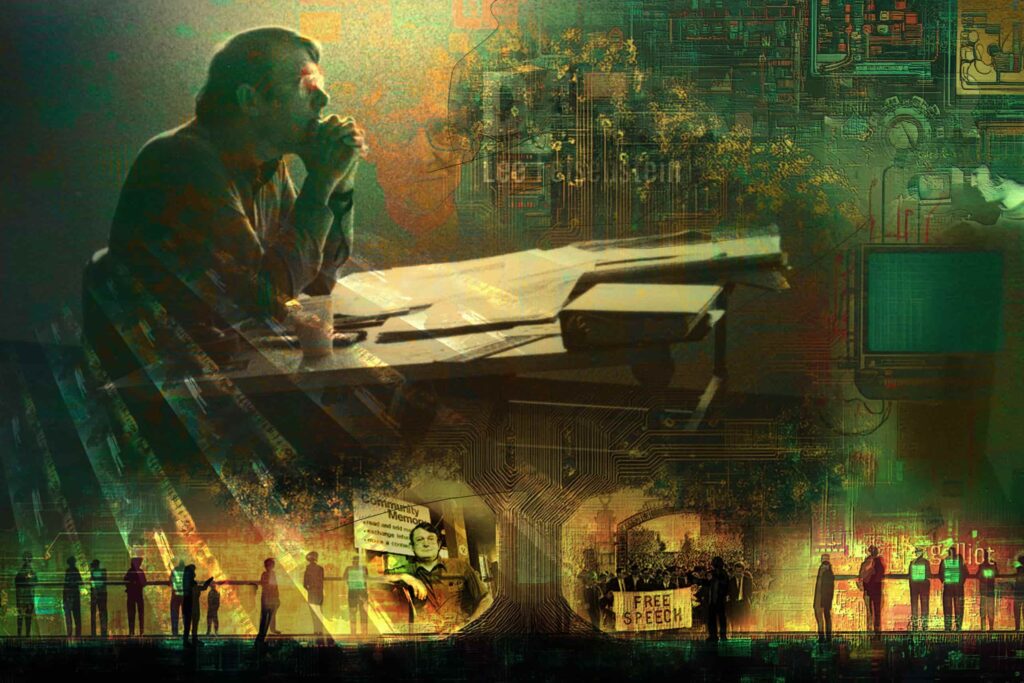

Lee Felsenstein, who Started The Digital Revolution (I’m Exaggerating a Little); Declares the Golden Age of Engineering

Oct. 24, 2024. 17 mins. read.

29 Interactions

Lee Felsenstein, a key figure in the evolution of personal computers, explores the rise of social media, AI’s shortcomings, and the golden age of engineering in his new book.

Yes, I exaggerate. No one person started the Digital Revolution. But Lee Felsenstein was (and is) a key figure in the evolution of personal computers and social networking. His book Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media and the Future is a cross between a conventional autobiography and a historic discourse about digital culture: where it’s been, where it’s going, and what is to be done.

Felsenstein’s roots are in the Free Speech movement in Berkeley, California, where, among other things, he wrote for the radical left counterculture underground newspapers Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe. As a means of increasing communication and community in Berkeley, in 1973, Felsenstein developed Community Memory, an early social networking system that existed on computers located in public places around the town. He was also one of the main progenitors of the Homebrew Computer Club, which started in Menlo Park California in 1975.

This is the scene where many important early computer hobbyists met up and started working and playing with, and around, the first reasonably priced microcomputer, the Altair 8800.

The Homebrew Computer Club might be most famous for being the club wherein Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs showed off their early work on what would become the Apple. Felsenstein was not very impressed, finding developments by other tinkerers more exciting. This is the sort of deep history of the digital revolution you will find in this revealing, personal, technical, and highly entertaining and informative book. I urge you to run out (or log on) and get it immediately.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)

4 Comments

4 thoughts on “Lee Felsenstein, who Started The Digital Revolution (I’m Exaggerating a Little); Declares the Golden Age of Engineering”

Lee Felsenstein's insights remind us how innovation and community-driven engineering sparked the digital revolution, inspiring today's creators to continue pushing the boundaries of technology!

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

This was really amazing, very insightful.

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

I’d never heard of the chap. “Computers are great at counting beans.” Oi, the bottle he’s got! I’ll definitely give his book a look. Cheers, RU—hats off as usual.

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

Internet communication is either dying or evolving. Dying: true communication between real humans is no longer the majority on social media platforms or in any online groups. Conversations are synthetic, artificial, or calculated, generated by AI or paid human trolls: even amoung true humans genuine conversation is rare and Mos of it fake, calculated for 'attention', utterly stupid garbage, outright copy paste, or useless mantra.

Evolving: communities and conversations are growing in volume and visual effects. Evolving for good? I don’t think so. But I’m in my 30s, so what do I know about the new generation?

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩