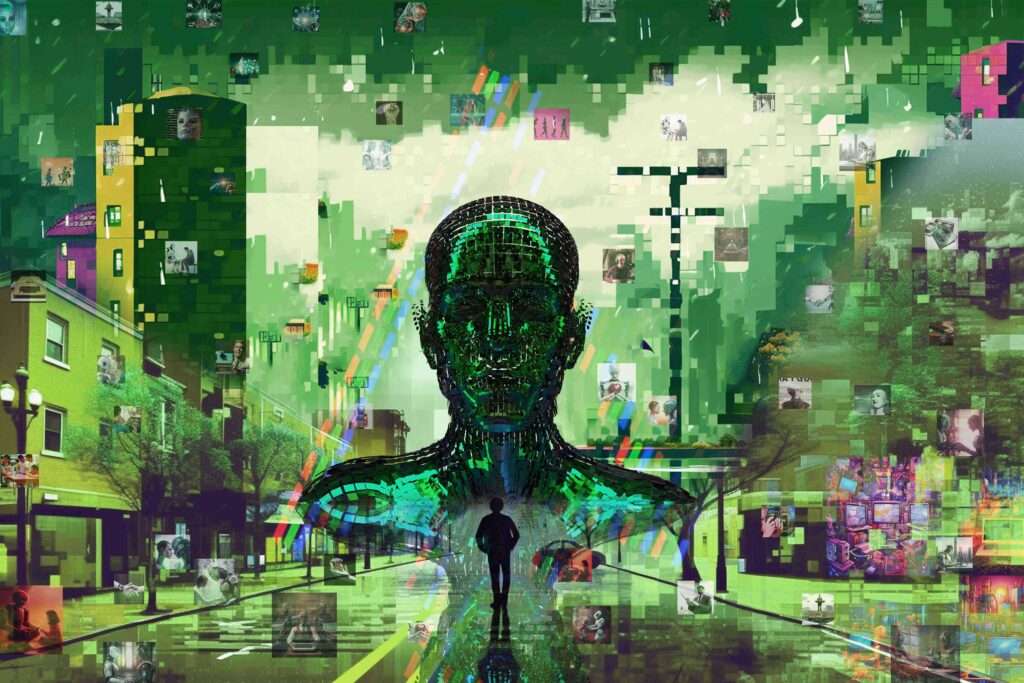

“Cyberculture” — the embrace of rising digital technology in the 1990s — was attractive to the hip (a word which, according to some, translates into “knowing”). Avant-gardistes are instinctive lovers of risk, always experimenting with the new; always pushing the broader culture forward while pushing its triggers.

The culture then was at once kindly and brutal. It promised to inform the masses; to give the average person open access to the means of communication — taking it away from the monied, well-connected elites. It touted production technologies that could end scarcity — at the extreme, there was the oft-expressed hope for achieving Drexlerian nanotechnology. This sort of nanotech could, in theory, program matter to make whatever was needed or desired. (They promised me a self-replicating paradise and all I got was these lousy stain-resistant pants.) Declarations about scientists having achieved cold fusion for clean energy were known to be dubious, but surely were indicative of breakthroughs to come.

The hacker ethic, as it was then understood, was all about making everything as free as possible to as many people as possible. Data, at least, was to be free really soon. Unlike physical goods, you can copy and share bits of data and still have it yourself. Over the internet, one could share it with everyone with internet access. There was to be no scarcity in anything that was made from data. In theory, with the kind of advanced nanotechnology advocated by Eric Drexler in his 1986 book The Engines of Creation, you could share data over the internet that would self-create material commodities. Today’s 3D printer is a primitive version of the idea of turning data into material wealth.

On the flip side of all this noblesse oblige was the arrogance of those who ‘got it’ towards those who didn’t. And hidden within the generous democratic or libertarian emphasis of the cultural moments was the contradictory certainty that everyone was going to have to participate or wind up pretty-well fucked. Stewart Brand, very much at the center of things (as mentioned in earlier columns) wrote, “If you’re not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road.” Note the brutality of this metaphor. In other words, the force that was promising to liberate everyone from the coercive powers of big government and big money — to decentralize and distribute computing power to the masses contained its own coercive undertow. Brand was saying you would be forced (coerced) into participating with the digital explosion by its inexorable takeover of economies and cultures.

On its inception in 1993, Wired Magazine shouted that “the Digital Revolution is whipping through our lives like a Bengali typhoon,” another metaphor for disruption that sounded exciting and romantic but is basically an image of extreme material destruction and displacement. In my own The Cyberpunk Handbook, coauthored with (early hacker) St. Jude, we characterized the “cyberpunk” pictured on the cover as having a “derisive sneer.” Much was made of the cyberpunk’s sense of having a kind of power that was opaque to the general public. Hacker culture even had its own spellings for people who were a million times more talented with computers and the online world than the “newbies’ — eleet, or 31337 or *133t. Technolibertarian (and Mondo and Wired contributor/insider) John Perry Barlow whipped out the line about “changing the deck chairs on the Titanic” every time the political or economic mainstream tried to even think about bringing the early chaos under some semblance of control. In 1995, he wrote A Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace, declaiming, “I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

Barlow imagined cyberspace as a separate state largely unconnected to the realities of governments and other concerns of the physical world, an idea that seems preposterous now that access to the internet is pretty much a requirement to get work, transfer moneys, and access most medical services.

Even the mainstream’s shiny young boomer president, Bill Clinton, told people that the average person would have to “change jobs seven times” in the new economy (from burger flipper at McDonalds to Barista at Starbucks to lap dancer and back again). He tried to make it sound like it was all exciting, part of changing times, and he and the more directly cyberculture-oriented VP Al Gore touted retraining as a solution for the displaced (Has retraining been replaced with re-education among the “center-left” politicians of the fading neoliberal consensus? A case can be made.)

As in all these cases, there was not much thought or sympathy for vulnerable people who might not be in a situation or condition that would allow them to cope with this jazzy and exciting rapidly changing future. Which brings us to…

The Precariat

“We are the 99%.”

Class in America has always tended to be unspoken and, during the pre-digital age, there was a strong, comfortable middle class. My own parents, born in the mid-1920s and right in the middle of the middle, never feared slipping into poverty or homelessness. They bought homes. They rented. The cost wasn’t absurd. They got sick and were kept overnight in hospitals without having their savings wiped out. There was a comfortable sense that there would always be a nine-to-five job available with modest but adequate pay and benefits. And there was an additional sense that the companies or institutions they would work for were solid. Whatever it was, it was likely to remain open, functional and not inclined towards mass firings. They wouldn’t have to “change jobs seven times”as suggested by President Clinton.

The idea of a class called the “precariat” — a portmanteau of ‘precarious’ and ‘proletariat’ — was popularized by the economist Guy Standing to describe the increasing numbers of people who lack predictable work or financial security. The precariat need extra work (’side hustles’) to bung the gap in their income: gig work, underground economic activity, and extended education or that good ol’ Clintonian ‘retraining’. Members of the precariat mint lines of NFTs hoping they will haul them out of precariousness, or at least give them a temporary lifeline. Ride-sharing businesses can only exist where there is a precariat.

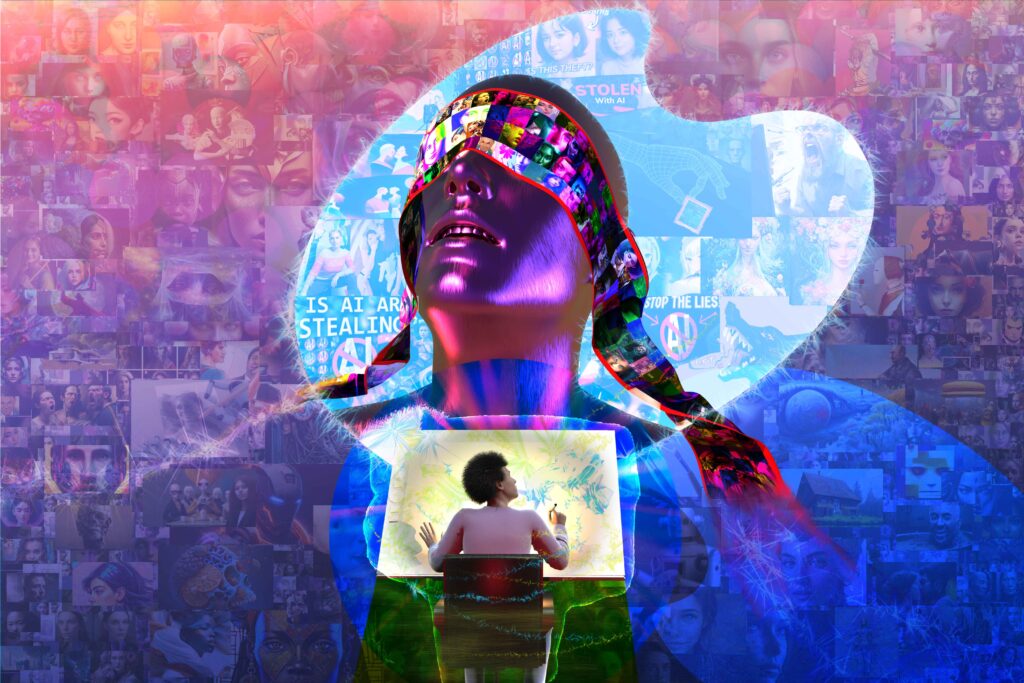

There is an equal or perhaps greater cause for precarity in the state’s hands-off approach towards monopolies, and to what Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow call ‘monopsonies’ (they didn’t originate the word). Wikipedia explains this economic trap as where “a single buyer substantially controls the market as the major purchaser of goods and services offered by many would-be sellers.” Amazon is a world-historic example. The backlash is directed towards digital technology as a whole – rather than just Amazon or some other monopoly company.

Occupy Wall Street & the 99%

Although the people who initiated Occupy Wall Street probably were not using the term back in 2011, their genius was in recognizing that precarity could be as high as 99% of the public – as middle class, upper middle class and even a few wealthy investments crashed, homes went “underwater,” business folded etc. When Occupy started and gained attention, some polls showed that a greater percentage supported than opposed the movement (44% versus 35% according to this Pew Research.) This may not seem impressive but it was a good stat in a land where most people are persuaded that they can achieve “the American dream” with hard work and good luck.

Identity: We Are Not The 99%

Many blame social media for spreading hostility among the public, both in the US and elsewhere. And there can be no doubt that seeing what huge numbers of other people have on their minds is the most irritating thing imaginable. (Cyber-romantics of the 90s rhapsodized the idea of a noosphere — a kind of collectivized global brain. On learning what’s going on in a lot of brains, I would suggest that this idea was, at best, premature. Detourning Sartre for the digital age: Hell is other people’s tweets.) Still, dare I suggest that there was a quantum leap in emphasis on identity divisions and anxieties in the immediate aftermath of Occupy? Was there, perhaps, a subterranean effort to convince us that we are decidedly not the 99%? I try to stay away from conspiracy theories but the thought nags at me.

Not Happy To Be Disrupted

As I noted in an earlier column, a lot of people, living in precarity, are not happy to learn about new disruptive technologies. More people, including many who were techno-romantics back in the 90s, now feel more like the road than the steamroller in Stewart Brand’s metaphor. Programmers are now panicking about losing jobs to AI and I hear talk that some in the libertarian bastion of Silicon Valley are opening up to more populist ideas about engaging the state in some form of guaranteed income security.

A follow up column Risk and Precarity Part 2: The Age of Web3 will follow.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)