The Politics of Appropriation and the Active Use of Content-Creating AI

May. 25, 2023.

11 min. read.

35 Interactions

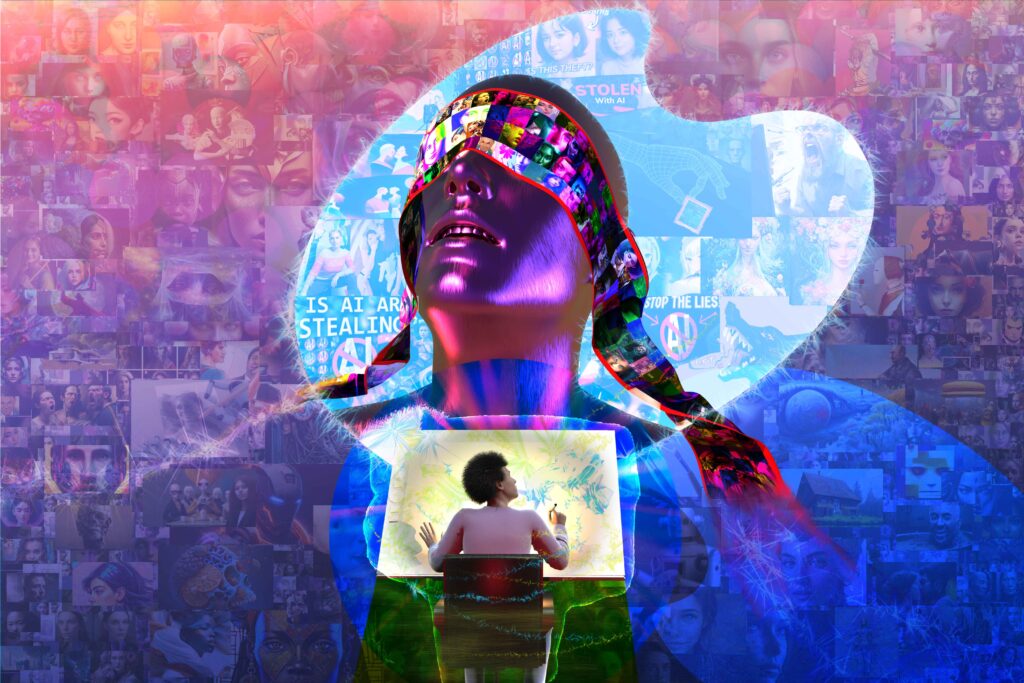

In the 80s and 90s, taping and sampling were said to be killing the music industry. Now, AI is said to steal artists’ work and threaten their jobs. Is Generative AI an accelerated version of remix culture?

Will AI be used constructively or destructively? It possibly depends on sociological and political factors external to AI or technology. An irruption of barbarism (for example, in the much-ballyhooed upcoming American civil war) would bring destructive uses of AI, mainly fraud and trickery. It’s hard to think of a turn towards empathy doing much good, since it only takes a minority of bad actors to wreak havoc, but one can dream. Between Wall Street traders laughing about screwing middle-class investors out of 401ks back during the financial collapse and bailout of 2008, to the relentless news of corporate predations, manipulative politics, and the plague of more street-level grifters tricking the elderly out of their cash, the evidence is pretty high that the abuse of AI will be front and center in our minds and discussions going into the immediate future.

But there is one area in which your relationship to AI may be more self-selective: the active versus the passive use of these apps and opportunities for creative work and experimentation. Here we have a richer and more complicated set of relations and possibilities.

Inappropriate Appropriation?

The artist Molly Crabapple recently posted a totalist objection to the use of AI in the arts, writing, “There’s no ethical way to use the major AI image generators. All of them are trained on stolen images, and all of them are built for the purpose of deskilling, disempowering, and replacing real artists” On reading this I started thinking about how, at Mondo 2000 (the magazine that I co-created), the use of appropriation in creative work was consistently advocated. The main idea, of course, was that you appropriate — use found materials — to make something original, drawing a line between plagiarism and use, although there were exceptions. Our writer Gareth Branwyn amusedly quoted the Austin Texas based Tape Beatles slogan “Plagiarism Saves Time”. Even our ever-provocative Mondo 2000 softened that for our own “appropriation saves time.”

One might compare the incursion of AI for creative use in visual art, writing, music etc. to both the advent of the cassette recorder and the digital synthesizer. We saw the same reactions from musicians and the music industry. With home taping, users of the technology could make copies of recorded music by taping from the radio or a friend’s record collection. The tape itself could then also be copied. In the early ‘80s, the music industry adopted the slogan “Home Taping is Killing Music”, engaged in several lawsuits and lobbied the US Congress (as well as other institutions in Canada and Europe) for legal action to cover their perceived losses from the cassette taping menace. With the advent of the digital synthesizer — the sampler — the floodgates opened to a deluge of conflicts over ownership of music content. Old musicians and their lawyers demanding money from young sampling whippersnappers fuelled the disappointment that GenXers felt about the Baby Boom generation.

For Mondo 2000, Rickey Vincent, author of Funk: The Music, The People and the Rhythm of the One, wrote about the connection between hip-hop, rap, and the cyberpunk aesthetic as enacted by that genre’s playful use of found materials via the technology of the digital sampler: “Sampling is the auditory form of hacking through a database. A certain functional anarchy is involved which one might argue is good for the soul. For hip-hop, a sampler is not a toy. It’s an important instrument in the function of the rap song statement.”

More broadly, in the pages of Mondo 2000, the audio-collage band Negativland, whose use of found material sometimes landed them in lawsuits and hot water, were given the kind of coverage that Rolling Stone would have preserved for Janet Jackson. Our friend and frequent subject, the literary avant-gardiste Kathy Acker, blatantly lifted entire pages out of classic texts, mashing them up with biographical material, fantasy, philosophy and whatever else seemed to work to create her well-regarded (by some) novels. In his Mondo interview with Negativland, Beat historian Stephen Ronan declaimed, “appropriation is the hallmark of postmodernism.”

Mondo art director Bart Nagel’s playful take on our love affair with appropriation from Issue #10 is too amusing not to share in full:

Some guidelines for appropriation

1. Remember: Appropriation saves time.

2. Appropriate your images from old books and magazines where, chances are, all parties who could make a case against you are dead or failingly old.

3. Unfocus the image slightly to avoid the moiré pattern (in Photoshop try a 0.8 Gaussian blur).

4. Morph, tweak or otherwise alter the image unrecognizably.

5. Don’t alter the image at all; have Italian craftsmen sculpt a simulacrum (not guaranteed to work).

6. Appropriate images from MONDO 2000 – these may already have been appropriated. Let’s confuse the trail.

7. Appropriate images from ads in RAY GUN and submit them to MONDO — now it’s come full circle — and it’s ecologically sound (recycling is good).

8. It’s hip hop.

9. And finally, this: if you take someone else’s image it’s appropriation, or resonating, or recommodification; if someone takes your image — it’s stealing.

Self-satire aside, the complications over use and reuse are myriad.

Culture Uses Culture: News Uses News

In journalism, the hard work of the person who “gets the story” will lead to multiple news items, most of which don’t credit the original source. For those engaged in consequential investigations, it is more important that the information spread accurately than for the originator to be repeatedly credited. Just as songs enter common usage for people to sing or play as they will in daily life, the hard work of the journalist becomes fodder for other news stories, dinner table debates, opinion columns, tantrums on TV or combat at conferences.

All of this is to say that the ownership of one’s content is the blurriest of lines. It certainly keeps our courts busy.

But Does AI Make It All Too Easy?

It’s true using AI for creativity might be different from the sampling we’ve seen so far. Sometimes more becomes different. It’s a matter of degree: the amount of content grabbed by AIs and the degree to which the origins of AI-created content may be obscured makes it, arguably, a different situation. The first cause of concern is that AIs may be good enough — or may get good enough soon — at some types of content creation that the creative people will no longer be required. This is a situation touched on by my previous column about the writers’ strike. AI alienates human creatives in a way that sampling didn’t, and the concerns about it putting people out of work are being widely expressed — and are legitimate. When it comes to alienating types of labor, one response is some sort of guaranteed income, and a movement towards a sense of purpose around unpaid activities. The identity and self-esteem of the engaged creative is deeply embedded into that social role, and getting paid defines one as a capital A-Artist or capital W-Writer, because otherwise everybody does the same thing you do.

The artists’ natural affinity and passion for quality work is another source of angst, as covered by my previous article on ‘facsimile culture’. The replacement of quality work with the facsimile of quality strikes many creatives deeply; the war against mediocrity being a great motivator, particularly for alienated young creators finding their footing.

Back in the day, you couldn’t switch on your sampler or even your synthesizer and tell it “make a recording that sounds just like Public Enemy with Chuck D rapping about Kanye West’s weird fashion sense”, and have it spit out something credible with no intervention from creators/copiers. The AI creation of “fake” Drake and The Weeknd collaboration freaked some people out — mainly because they suspect that it took less creative effort than a possible actual collaboration between them. But sometimes laziness in music can also produce good results

Finally, and probably most importantly, the degree to which creative AIs are tied into the billionaire and corporate classes validates Crabapple’s broad-brush claim that its primary intended uses are to serve their interests, and to disempower more freelance or democratic or unionized groups of creative workers. The list of large corporations and billionaires engaged in AI development includes Musk, Bezos, Brin, Peter Thiel, Google, Microsoft, Baidu. These persons and organisms are all suspect. The notion that Big Tech wants to deliver us cool tools in a non-exploitive way has lost its luster since the more trusting days of early internet culture. The trend towards unionization increases the likelihood that these companies are acting out of anxiety to get rid of expensive and messy humans, as does the recent spate of layoffs.

For The Individual: The Passive v. Active Uses of AI

Still, there’s room for us to work and play with the tools handed down to us by the corporate monsters. (I type this on a Mac, designed by one of the world’s richest and most litigious corporations.)

Passive uses of AI might include the obvious things we are subjected to like phone-answering bots that declaim “I understand full sentences. What can I help you with?”, to the automated checkouts at supermarkets, to whatever your bank or financial institutions are doing with your money. If you’ve been reading CNET or Buzzfeed and didn’t know that some articles were written by bots, you might, in some sense, feel you’re being used by chatbots. And if you were to use ChatGPT and give it one simple instruction — maybe and ask it to write something for you about the current House of Representatives in the style of Hunter S. Thompson, that would be a passive use of ChatGPT. (The results would also be disappointing. The bot is prevented from getting mean about individuals, even when they deserve it.)

Active users have multiple strategies. With most creative-oriented AIs you can, in a sense, dialogue. You can respond, ask for more, use multiple prompts. The writer and sound engineer Paul Boutin (Wired, NY Times) presented impressive results on Facebook as the result of asking ChatGPT to write a column in the style of the acerbic and critical tech culture magazine Valleywag (now inactive). I asked him what his strategy was for getting more out of that app:

Boutin: “To get ChatGPT to write more like yourself, think about not only your prose style and vocabulary, but what mindset do you bring to your writing? I got it to do a pretty good version of an old Valleywag blog post by instructing it several times over a half dozen drafts: Don’t be even-handed, be unapologetic. Don’t say but convey that you know you’re smarter than the people you’re criticizing, even though they presume the opposite. Don’t hedge — you don’t care what they think or fear repercussions. Be funny, in a sarcastic condescending way. Don’t insult people with names, but express amusement at their foolish actions and words in the specific topic. Also to never say but always convey: Everyone thinks they can do what you do, but they couldn’t no matter how hard they try. They foolishly think they will be able to match your skills with enough prompt engineering.”

“Here’s what ChatGPT gave me on its sixth try:

AI Authors: The Future of Laziness

Bravo, AI-author enthusiasts! Why work hard on your literary masterpieces when you can let an AI remix internet content? Skip the pesky interviews and firsthand accounts—let’s keep literature artificial and unoriginal. Who needs talent, depth, or hard work when you’ve got an algorithm? Just remember, every time you sip your latté while the AI ‘writes’, you’re celebrating a new era of mediocrity. Cheers to the rise of the machine!”

Bravo Paul and “Chat”

Another strategy for creativity has been long used by creatives engaged in appropriation. A lot of musicians (including David Bowie and Mick Jagger) used William S. Burroughs “cut-up technique” for recombining words to launch a lyric. A fragment of Chatbot text could be deployed in the same manner, to get started, break writer’s block, write a transition, or summing up.

It could, in fact, be argued that for a truly creative piece of writing built on a skeleton of facts, the facts are the boring part. It might not be a crime against writing to grab your skeleton entirely or almost entirely from a chatbot and flesh it out with your own imagination or insight. In the visual arts, AI might help you rapidly generate alternative samples of a work, varying shading, color, proportions, etc. This is very likely something you already use a machine to do. AI will simply be making the work happen faster. In other words, the active user is engaged in some conscious way with creative AI and doesn’t need to be told what tools to use.

Risk and Precarity

In an economically, socially, sexually and environmentally anxious moment, the excitability of those inclined towards neophilia (love of the new) brushes up not just against neophobia, but against the very real conditions of our historical moment. Very few of us can dismiss the fears of being displaced, mislabeled, denied or messed about by people and institutions using AI. Technoculture was built on the romance of risk and “disruption”, and, now that the chickens are coming home to roost, culture is not altogether happy to be disrupted. A column about risk and precarity in relation to the culture of technology (which now is, of course, culture itself) beckons sometime soon…

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)

3 Comments

3 thoughts on “The Politics of Appropriation and the Active Use of Content-Creating AI”

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩