Firesign Theatre: The Greatest Satirists of 20th Century Media Culture and its Techno-romanticism were… Not Insane! An Interview with Jeremy Braddock

Nov. 15, 2024. 25 mins. read.

17 Interactions

R.U. Sirius and Jeremy Braddock revisited the legacy of Firesign Theatre as countercultural satirists and early techno-geek icons.

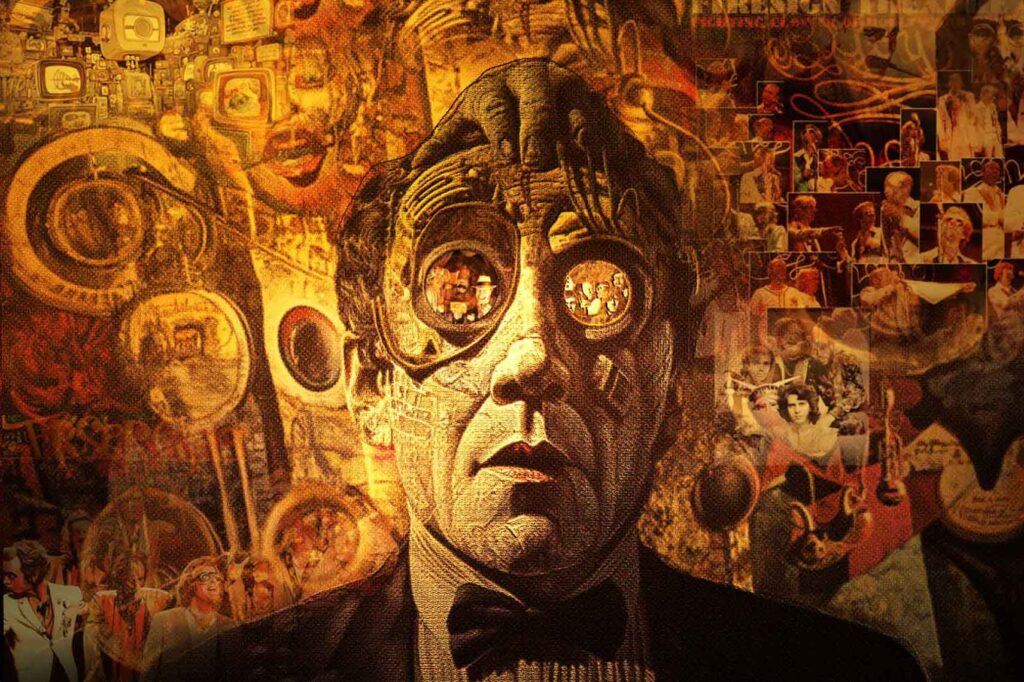

If you were a college student or Western counterculture person in the late 1960s-70s, the albums of Firesign Theatre occupied more space on your shelf and in your hippocampus than even The Beatles or Pink Floyd. If you were an incipient techno-geek or hacker, this was even more the case. Firesign was the premier comedy recording act of the very first media-saturated technofreak tribe.

In his tremendously informative and enjoyable history of Firesign Theatre titled Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as told in Nine Comedy Albums, author Jeremy Braddock starts by giving us the roots of a band of satirists that started out (to varying degrees) as social activists with a sense of humor. He shows them slowly coming together in Los Angeles while infiltrating, first, the alternative Pacifica radio stations like KPFK in Los Angeles, and eventually, briefly, hosting programs in the newly thriving hip commercial rock radio stations of the times, before they lost that audience share to corporatization.

Braddock takes us through the entire Firesign career and doesn’t stint on media theory and the sociopolitics of America in the 20th century that were a part of the Firesign oeuvre.

For those of us out in the wilds of the youth counterculture of the time, without access to their radio programs, it was Columbia Records albums that captured our ears and minds, starting with Waiting For the Electrician or Someone Like Him in early 1968. Their third album, Don’t Crush That Dwarf Hand Me the Pliers sold 300,000 right out of the gate and, in the words of an article written for the National Registry in 2005, “breaking into the charts, continually stamped, pressed and available by Columbia Records in the US and Canada, hammering its way through all of the multiple commercial formats over the years: LPs, EPs, 8-Track and Cassette tapes, and numerous reissues on CD, licensed to various companies here and abroad, continuing up to this day.” As covered toward the end of the book, they have been frequently sampled in recent years by hip-hop artists.

My introduction to Firesign came as the result of seeing the cover of their second album How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All in the record section of a department store in upstate New York. It was the cover, with pictures of Groucho Marx and John Lennon and the words “All Hail Marx and Lennon” that caught my eye.

It was the mind-breaking trip of Babe, as he enters a new car purchased from a then-stereotypical, obnoxiously friendly car salesman, and finds himself transitioning from one mediated space to another, eventually landing in a Turkish prison and witnessing the spread of plague, as an element of a TV quiz show.

The album ends with a chanteuse named Lurlene singing “We’re Bringing the War Back Home.” This was all during the militant opposition to the US war in Vietnam. Probably few listeners would have recognized “Bring The War Home” as the slogan of The Weatherman faction of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), but Braddock gets it, like he gets the seriousness of Firesign’s satire. Indeed, Braddock notes that several reviewers, writing with appreciation about one of their albums, averred that its dystopia was “not funny.”

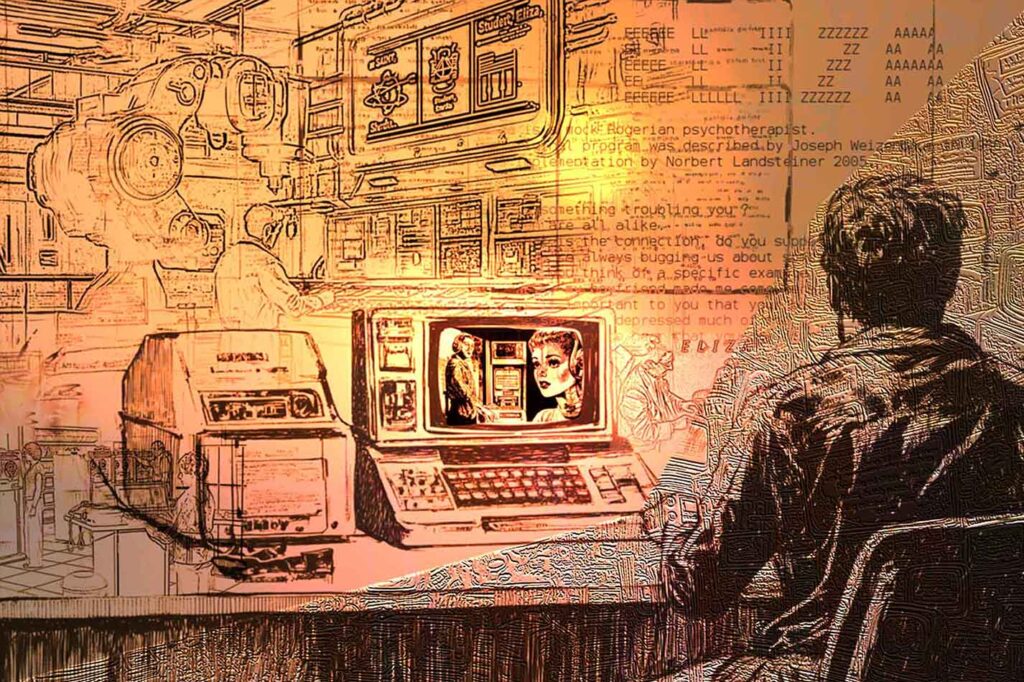

Most fans would agree with me that the peak of the Firesign run on Columbia Records was the exceedingly multivalent Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers and the futuristic, AI-saturated I Think We’re All Bozos on this Bus, which I note in this interview predicted the future better than any of the self-described futurists of the 1970s. But to apprehend the richness of those two psychedelic assaults on the senses and on the idiocracy of its times, you will need to read the book and listen to the recordings or at least read this interview.

Jeremy Braddock is, in his own words, a literary scholar and cultural historian specializing in the long history of modernism. (What? Not postmodernism!?) He teaches literature in English at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. I interviewed Braddock via email.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)

5 Comments

5 thoughts on “Firesign Theatre: The Greatest Satirists of 20th Century Media Culture and its Techno-romanticism were… Not Insane! An Interview with Jeremy Braddock”

This insightful exploration of the Firesign Theatre brilliantly captures their unique blend of humor, media critique, and cultural commentary. Braddock’s deep dive into their history not only highlights their artistic genius but also contextualizes their work within the sociopolitical landscape of the 1960s and 70s. A must-read for anyone interested in the intersection of comedy, technology, and counterculture!

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

Thank you R.U. Sirius for this informative interview, especially about Jeremy's writing process for Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums. I'm honored and humbled to have been included in the book. My fanzine Chromium Switch was just one of many to follow in the logical extension of Firesign Theatre fandom.

"You’ll be getting a handsome simulfax copy of your own words in the mail soon"

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

Could there be a comedy group that looked more like Sly and the Family Stone or Prince and the Revolution, but with the democratic give-and-take of the Beatles?

Yes, but they wouldn't be funny.

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

Great

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩

Thank you gentlemen, it is a lovely read. It is sad to know current science is dominanted by deterministic views. Humanity thrives where there is a choice.

Here are some slogans of mine that scares me more: we are heading toward a future that has less and less room for individual choices.

Politics: Power manipulates – Policies deceive – Citizens obey!

Capitalism: Wealth constructs – Systems enslave – People comply!

Religion: Faith fabricates – Dogmas dominate – Souls submit!

🟨 😴 😡 ❌ 🤮 💩