Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

SocialFi: Trade Friends and Influence People With These Five Projects

In a recent article we discussed the rising popularity of social finance, also known as SocialFi or SoFi) in 2023. This fun and experimental new way of monetizing social networking has helped crypto degens entertain themselves during a bearish last 12 months, while providing a compelling new use case for Web3.

Much of this year’s hype has circled around Friend.tech, which tokenizes social media accounts kind of like a stock (don’t tell the SEC) and allows account holders to create monetized membership groups in the process. There has been a bit of controversy around its founders’ background and their role in a failed previous project named Kosetto (giving off some Do Kwon and Basis Cash vibes), however, it has certainly picked up organic traction despite this.

Project 1: Friend.tech (Base)

What is it?

Friend.tech is a decentralized platform for monetizing your social influence through tokenization. Built on the Base Network (a layer 2 network developed by Coinbase), Friend.tech allows users to own, tokenize, and trade Twitter profiles.

How it works

Friend.tech allows users to tokenize their online influence and attention and trade it as a token. The token was renamed from ‘Shares’ to ‘Keys’ in August. These Keys grant holders exclusive access to the app’s built-in chat rooms and content from creators. Fans can support content creators by buying shares in their profiles in the form of ‘Keys’.

Friend.tech users have chat groups that are similar to other apps such as Telegram. However, the difference is that group members must purchase Keys in order to access the group. A holder can sell the Keys if they want to leave the group, or earn a profit by trading the ‘Keys’.

Team

Friend.tech was created by pseudonymous founder 0xRacer and his anon team.

They’d pulled in over $40 million in revenue by October 2023 and the app was at the time considered the biggest revenue-generating dApp on the Base network, and astonishingly, the 2nd biggest in all of crypto. It’s no surprise then that a plethora of copycat projects soon tried to emulate their success.

Project 2: Stars Arena (Avalanche)

Stars Arena is a fork of Friend.tech, built on the Avalanche network instead of Base. It is a decentralized social finance platform that allows creators to monetize their work and enables followers to connect with their creators.

Main Purpose

The purpose of Stars Arena is to give creators a platform where they can monetize their content. Creators sell Tickets (similar to Friend.tech’s Keys), which equate to shares of their platform, to their followers. Followers can buy and sell the creators’ tickets using the AVAX cryptocurrency.

How Stars Arena Works

Stars Arena allows users to have fractional ownership of Twitter profiles of content creators, influencers, or celebrities. By purchasing Tickets, users have the right to engage with content creators in a more personalized way.

Ticket holders can communicate with content creators via direct messages. Content creators can upsell the price of their Tickets by using various methods such as offering valuable info with restricted access. The platform has a tipping feature that enables users to reward creators.

Stars Arena has a referral program where users can refer their peers to the platform and earn a 1% commission on every trade made by their referrals.

Stars Arena Team

Stars Arena was launched by an anonymous developer with the Twitter handle @hannesxda.

Project 3: Open Campus (BNB Chain)

Open Campus is a decentralized education-focused social platform that brings educators, content creators, parents, and students under one roof. The Open Campus protocol is powered by the $EDU token. Built on the BNB network, the EDU token can be used for:

- Paying content creators for their revenue share

- Minting NFTs from educational content

- Voting rights within the Open Campus ecosystem

Main Purpose

Open Campus is a platform that uses blockchain technology to build an education ecosystem. The platform decentralizes the creation of educational content so that students can access a wide range of learning material.

How Open Campus Works

Open Campus uses social incentives to promote the creation of valuable educational content. The platform works on the following premise:

- Digital rights – educational content is minted as non-fungible tokens (NFT) to enable the wider community to participate in alternative, decentralized learning.

- Decentralization – users can create and consume content whenever it suits them.

- Immutable records – the platform uses blockchain technology to ensure that certificates and qualifications are permanently recorded on the blockchain, and can be easily verified.

By launching educational content as NFTs, content creators and their partners can earn revenue based on their contributions.

Open Campus Team

TinyTap, an Israeli company founded in 2012 by Yogev Shelly and Oren Elbaz, acquired Open Campus. Open Campus counts Animoca Brands, Mocaverse, The Sandbox, Hooked Protocol, and GEMS Education as its partners.

Project 4: Hooked Protocol (BNB Chain)

Hooked Protocol is an edutainment network that utilizes gamified and immersive learning experiences to accelerate Web3 mass adoption.

How Hooked Protocol Works

Built on the BNB Chain, Hooked Protocol has bespoke Learn & Earn products that act as an on-ramp for attracting Web2 users to Web3.

The platform has built the following products to educate users about Web3:

- Quiz-to-Earn

- PoWT (Proof of Work and Time) Mining Game – a game that rewards users for contributing their effort and time to the Hooked Protocol ecosystem.

- Social referrals – users are incentivized to invite other users to the platform

- Stake and Swap – users can use the ecosystem’s wallets to stake and swap their crypto.

$HOOK, a BEP-20 token, is the platform’s governance and utility token. It has a market cap of nearly $50 million as of November 2023.

Hooked Protocol Team

Hooked Protocol founding and leadership team consists of three known people:

- Founder – according to LinkedIn, founder Jason Y has over ten years of experience in internet and growth strategy.

- CTO – Mike Y has strong engineering skills that encompass financial services and consumer product development.

- CMO – Jess L, who previously worked for leading tech firms in Silicon Valley, is proficient in marketing, strategy, and business development.

Hooked Protocol enjoys financial backing from Binance Labs and Sequoia.

Project 5: Twetch (Bitcoin SV)

Twetch is a pay-to-earn Web3 social media platform where creators earn money for their content, and every bit of information is stored on the blockchain.

How Twetch Works

Built on the Bitcoin SV network, Twetch rewards creators using BSV. Creators need to have a wallet to receive micropayments for follows, likes, replies, and reposts.

Users earn payments from connecting their Twitter accounts to Twetch and posting from there. Users have to pay to post on Twetch, something that may discourage Web2 social media users who are used to posting for free. Every action on the Twetch platform needs to be paid for, since it is on-chain and incurs mining fees.

The native currency of Twetch is called Twetch Coin. Twetch also has an NFT marketplace and other features that include a BSV wallet, chat functions, and a jobs board.

Twetch Team

Twetch was co-founded by Billy Rose and Joshua Petty, who also serves as the CEO. Petty, who attended Purdue University, is the CEO of Ordinals Wallet. Petty and Rose have previously joined hands to co-found several firms such as Coindex and Area21.

Conclusion

While the recent slew of half-baked SocialFi applications might seem an opportunistic shout into the Crypto Twitter echo chamber, there’s no doubt that entertainment-focused use-cases such as social media and gaming are potential keys to mainstream adoption for Web3.

By merging elements of the two and gamifying your social network interactions, SocialFi offers something unique and could be a precursor for the future of social networking.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Ten AI × Web3 Challenges That Blockchain Must Solve

In previous articles, we discussed the growing convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technology, as implemented in Web3, and the use cases of cryptocurrencies like SingularityNET’s AGIX token.

The integration of these new digital tech fields would seem to be rather straightforward, but it’s quite the opposite. It can be a complex or near-impossible endeavor which some experts like DeFi lord Andre Cronje deem to be a waste of time.

This is because blockchain serves to record historical financial data in a transparent and deterministic manner, while AI is a “black box” (in the words of Cronje) that delivers unpredictable results by design based on the input it receives.

As a result, there are several serious challenges that must be addressed to fully realize the underlying potential of AI and blockchain technology. Let’s take a quick look at ten of the most pressing issues.

Complexity

AI models traditionally have had a data collection problem; they have to connect to datasets from different parties. This can lead to interoperability issues, technical complexity, and a lack of unified standards. The same issues are also pop up in the blockchain and cryptocurrency sectors, which have created workaround solutions like cross-chain bridging. These are distinct but important technologies, still in an early stage of maturation, and they require specialized, costly expertise.

Scalability

AI applications often need high-speed processing and low-latency communication. This can be difficult to achieve on a blockchain network that has limited throughput and slow consensus mechanisms.

Blockchain networks also face the problem of scaling: storage and energy demands grow as the networks grow in size and complexity. Viable scalability solutions include the use of layer-2 and layer-3 networks, as well as sharding, something that Vitalik Buterin has touted as one of the three transitions Ethereum requires for global adoption. Ethereum itself will soon implement its EIP-4884 Proto-danksharding upgrade to make it easier for L2 chains to scale without compromising on transaction cost and data privacy.

Data Privacy and Security

One of the most important currencies of the modern era is data. It has been said that future wars will be fought over data, not oil, water, or gold.

Blockchain technology, known for its decentralized and immutable nature, presents challenges in handling sensitive data in AI applications. When AI algorithms are integrated with distributed ledger systems, sensitive data used for training models or executing smart contracts may be exposed to all participants in the network or to malicious third parties.

This raises questions about how data security and privacy are maintained. Data can be safeguarded through encryption and zero-knowledge proofs and ensuring strict access control.

Without addressing data privacy and security, generative AI models may struggle to be adopted by major businesses.

Skills Shortage

The rapid evolution of AI and Web3/blockchain often outpaces the availability of professionals with skills on the cutting edge. Artificial intelligence is rewriting the workbook as Goldman Sachs claims that the emerging tech will impact 300 million full-time jobs globally, yet this revolutionary industry suffers from a skills shortage.

As such, technical requirements have become the key challenge in scaling high-performance AI projects. The skills gap can only be bridged by educational programs and a lively community of learners. Upskilling in these areas is essential for addressing this shortage. AI companies need to appeal to white-collar employees by reiterating that AI is not just taking over jobs but creating new employment opportunities.

Regulatory Challenges

AI and blockchain/Web3 are disruptive technologies; they could change the world as we know it. Therefore, they face regulatory hurdles from genuinely concerned lawmakers, including some who just oppose the existence of these technologies. Elon Musk has voiced his concern, saying that AI must be regulated as it poses risks to civilization. Over 1100 tech leaders earlier this year signed a letter of concern over the rampant growth of artificial intelligence and called for responsible development.

The crypto industry has endured enough regulatory gaslighting from different authorities, and sometimes, the industry has frequently shot itself in the foot through shady individuals and corrupt companies. The industry needs to rebuild after flagship crypto entities such as FTX, 3AC Capital, Terra, etc. went belly-up in 2022.

Integrating AI in a blockchain company often involves dealing with regulatory challenges related to data privacy, security, and transparency. For AI and Web3 to thrive, it’s crucial for companies to find common ground with governments and regulatory bodies. AI and blockchain-specific regulations must provide clarity and encourage innovation within the confines of the law.

Lack of Standards

There is no set standard for integrating AI and blockchain, which can lead to problems with interoperability. This lack of uniformity may result in market fragmentation, which could stifle innovation and adoption.

Email became successful because it follows a common standard (called SMTP). A Gmail user can easily send and receive emails from Yahoo or similar services. The absence of clear standards in AI and Web3/blockchain can hinder development. Establishing universal standards for blockchain and AI protocols can facilitate smoother integration and collaboration across platforms.

After all, standardization leads to easier use, and by extension, wider adoption of AI and blockchain/Web3 technologies.

Decentralized AI Models

What if AI could leverage one of the major selling points of blockchains – decentralization? Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), tokenization, and market analysis and trading are all areas where decentralized AI models can be used to reduce the risk of single points of failure and enhance trust. Using blockchains to store and distribute certain kinds of data is one way to achieve this. Several AI-focused cryptocurrencies could provide viable solutions for building decentralized AI models.

User Adoption and Education

Mass adoption might prove the major roadblock for AI and blockchain. The period of preaching to the choir is over; AI and blockchain developers must build so-called killer apps that naturally attract the masses to these technologies.

For AI and Web3/blockchain to gain wider acceptance, user education is key. The public must be informed about the benefits and potential applications of these technologies.

This could come in the form of events, articles, and video content. The use of AI in the newsroom can also go a long way in writing factual, unbiased news articles that bring more people to AI and blockchain tech.

Demonstrating real-world use cases is the foundation for mass user adoption. They can’t meet the lofty goal of onboarding the next one billion users if they don’t offer practical apps that act as a bridge between Web2 and Web3.

On a positive note, companies are more interested in blockchain technology. A survey carried out in early 2023 revealed that nine out of ten businesses in the US, UK, and China are adopting blockchain technology.

Tokenomics and Governance

Tokenomics and governance are central to Web3/blockchain ecosystems. Many people and investors study the tokenomics of a project before they decide on whether they should invest in it or not. On the other hand, governance builds crypto communities by allowing individuals to vote on decisions that affect the community collectively.

Implementing effective governance models and clear tokenomics can enhance transparency, fairness, and the overall success of blockchain projects. This goes a long way in promoting blockchain projects.

Conclusion

AI, applied correctly, can greatly enhance the impact of Web3 in the coming years. Or the opposite could happen! While the challenges covered in this article would appear daunting, it’s normal for any new technology to have some teething problems in early years.

For example, think back at the early issues with mobile phones and 3G networks. And before that, remember getting online through dial-up? Getting it right early on with the right frameworks and ethical decisions may prove to be the biggest challenge of all.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Top 10 Use Cases of AI in Blockchain and Web3

There has been lots of noise about artificial intelligence this year. We have heard that it will forever change every aspect of our lives. The same things were previously said about blockchain technology, which uses decentralized networks to offer cryptocurrency incentives to participants.

The most prominent AI companies are still centralized Web2 behemoths like OpenAI, Microsoft, and Google, but there is increasing confluence between machine learning and blockchain as the world of business becomes more and more automated.

Here are a few of the best use cases for a marriage between artificial intelligence and blockchain in 2024 and beyond.

10. Supply Chain Optimization

A 2023 study revealed that 29% of small and mid-sized businesses lost over 15% in revenue due to supply chain disruptions, with an additional 31% reporting losses of 7-15%. An integrated system of AI and blockchain could transform supply chain and logistics operations by making it more efficient and transparent, and helping better decision-making.

Cutting-edge AI algorithms can predict demand, manage inventory, and automate specific logistics processes. This reduces costs and the risk of fraud and counterfeiting within the supply chain. For context, global companies lose $500 billion per year due to counterfeit products.

AI and blockchain in supply chain processes can reduce errors and optimize resource allocation. This helps companies do what they love most: save time and money.

9. Market Analysis and Automated Trading

The crypto market is notorious for volatility and can move faster than traders can react. In August 2023, cryptocurrency traders lost $1 billion in liquidations due to a sudden sell-off.

Can traders or artificial intelligence counter these liquidations? Absolutely. By analyzing market data, social sentiment, and news in real time, AI can make predictions about future market trends and help traders with more efficient trading, improved risk management, and potentially higher profits. AI can detect pump-and-dump schemes (which are prevalent in the crypto space) to protect traders and investors.

AI can help traders identify crypto narratives in the early stages. For example, AI could have helped traders foresee the rise of AI cryptocurrencies or SocialFi and its importance to the creator economy. By picking the top 20 AI cryptocurrencies in early 2023, traders would have made sizable profits.

The rise of crypto trading bots on Telegram and Discord is a true reflection of AI’s growing influence in crypto trading. We hear that crypto builders are in it for the tech. But the traders are in it for the money, and bot trading when done right could be a viable way of getting that lambo one day, if you know what you’re doing and get lucky.

8. Fraud Detection and Prevention

Blockchain is known for its robust security and transparency, but is not immune to acts of fraudulence such as market manipulation, fake trading volumes, and phishing scams. AI can help by detecting unusual patterns and behaviors within the blockchain to identify potential threats. By recognizing anomalies, AI can minimize fraud, whether it’s in unauthorized access to the blockchain network, identity theft, or financial transactions.

Of course, it’s not only crypto. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) claims that consumers lost $8.8 billion to fraud in 2022, a worrying 44% increase from 2021. If AI and blockchain can reduce this figure, hopefully, some U.S. regulators hellbent on destroying crypto may start to see the potential it carries.

7. Personalized Recommendations

We have been using personalized recommendations for longer than we think. But through the power of Web3, AI, and blockchain, personalized recommendations can be taken to a whole new level. AI can be used on blockchain data to understand user preferences, and to provide users with tailored recommendations for new crypto, Web3, and NFT projects.

As the Web3 revolution accelerates, a decentralized web could help users own their data and achieve one of the leading promises of Web3: full privacy.

Blockchain, a digital record, can be mined for insight into the provenance of the data that builds AI, addressing the challenge of ‘explainable AI’. This helps improve trust in data integrity and, by extension, in the recommendations that AI provides.

6. Data Analytics

Blockchains are immutable ledgers that provide rich data to analyze. AI can rapidly read, understand, and correlate data at incredible speed. This big-data processing brings a new level of intelligence to blockchain-based business networks, and centralized service providers will struggle to keep up.

By providing large volumes of data, blockchain helps AI provide more actionable insights, manage data usage and model-sharing. All these combine to make for a better and more trustworthy data economy.

5. Smart Contract Auditing

It is estimated that the past decade has seen more than $4.75 billion in financial losses in Web3, caused by smart contract security flaws, with some estimates going as high as $12.3 billion.

AI can audit smart contracts, ensuring they function as intended, and are free from vulnerabilities and errors. This level of automation and assurance is crucial for the reliability and trustworthiness of smart contracts within the blockchain.

4. RWA Tokenization

Tokenization is a key concept in blockchain and Web3. A report by digital asset management firm 21.co claims that tokenized real world assets (RWAs) – crypto’s buzzword for bringing traditional financial products to various blockchain networks – could grow to $10 trillion by 2030.

AI can be used to create and manage tokens, ensuring that they are secure and compliant with regulations. This use case opens up new opportunities for businesses and individuals to tokenize assets, including real estate, art, fiat currency, and more. Stablecoins are so far the most successful application of tokenization of RWAs.

3. Healthcare Data Management

Healthcare providers must collect, transfer, and store sensitive data. This poses a big risk to the security and privacy of their users. In 2023, U.S. medical giant HCA Healthcare suffered a breach in which hackers stole data belonging to 11 million patients. How can healthcare facilities ensure data protection and privacy?

AI-driven blockchain systems can create and maintain secure, immutable patient records. This streamlines data access for healthcare providers, and also ensures the integrity and privacy of sensitive medical information.

The use of AI in healthcare can extend to clinical trials and research. Blockchain’s transparency and security, combined with AI, can optimize the management of clinical trial data. This can enable researchers to accelerate medical discoveries.

To go back to the realm of supply chain optimization, AI can aid in tracing the origins and journey of pharmaceuticals using blockchain technology to prevent counterfeit drugs from entering the market. It is estimated that nearly $83 billion of fake drugs are sold globally per year.

2. Energy Management

Arranging the clean energy transition is a key issue of our time. AI can optimize energy consumption, production, and distribution by studying usage patterns and predicting demand, while P2P blockchain trading can enable businesses and individuals to buy and sell excess energy directly from one another.

The two technologies of AI and blockchain can also speed up the development of smart grids that can efficiently distribute and manage energy resources.

1. Gaming and Virtual Reality

As the gaming sector intertwines with blockchain, it is estimated that the market size of blockchain gaming will grow from $7.1 billion in 2022 to a projected value of $772.7 billion by 2032.

Just like anything else in life, you can predict the future of blockchain gaming by following smart money, aka venture capital. Venture capital firms invested more than $2.3 billion in Web3 gaming in the first three quarters of 2023, showing the sector’s strength and resilience amid a brutal crypto winter.

What role does AI play in Web3 gaming and virtual reality? Generative AI can create immersive and responsive virtual worlds, enhance blockchain in-game experiences, and even optimize game development processes.

From generating realistic non-player characters (NPCs) to predicting player actions, AI is revolutionizing the gaming and virtual reality industry within Web3.

Conclusion

It’s still early days for both blockchain and artificial intelligence, and both are rather unfairly misunderstood and maligned by the general public and media. Despite this, the evolving new economies around data, digital creators, and tokenized assets should solidify this alliance in the coming years, hopefully for the greater good. Blockchain establishes digital trust and proof, and AI can both benefit from it and boost its reach.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Crypto Bull Run 2024/2025: What Will Drive It?

Some content on Mindplex may include forward-looking statements pertaining to future anticipated plans, performance and development of companies and industries. Any statements on this website that are not statements of fact should be considered forward-looking statements. Statements in this website that describe a company’s business strategy, outlook, objectives, plans, intentions or goals, or the future performance of an economic sector, are forward-looking statements, and all such forward–looking statements are subject to certain risks and uncertainties that could cause actual outcomes to differ materially from those in such forward-looking statements. Nothing in this article, or any other on Mindplex, should be considered financial advice. Cryptocurrency investing is a high-risk endeavor, and Mindplex accepts no responsibility for any risks taken by the reader.

Introduction

The 2021 Bull Run was incredible. Many first-time millionaires were created from the mix of innovation, economic stimulus, and – yes – a touch of speculation from investors stuck at home. The pandemic, which induced quantitative easing from the USA (aka money printing), and increased access to global trading platforms such as Coinbase and Binance, created a perfect storm for explosive crypto valuations.

Examining future crypto-narratives and pondering how they will influence the next cycle will best position you for the upcoming bull run. According to many experts, it is just beginning to form. Bitcoin has been off to a blistering start from the 1st of January 2023, then had a bit of a lull mid-year, before it breached $35,000 during October (‘Uptober’ in crypto parlance). This is consistent with the potential for a massive 2024.

Bear market fatigue can make the days of up-only growth seem like a distant dream, and make you feel that crypto will never enter a bull market again. However, the global financial system is constantly shifting capital, attention, and manpower, and many factors are aligning that mark crypto as the center of the bullseye.

Let’s examine these fast-approaching events and understand how they are indicating now is the time to prepare for the next virtual asset bull cycle.

Bitcoin halving (April 2024)

You’ve undoubtedly heard of Bitcoin halving and how it reduces the Bitcoin mined from each block by half. This causes miners to receive half of the previous reward, simultaneously reducing the inflow and incentivizing them to HODL until Bitcoin prices increase. This event is programmed to occur every four years until 2140, when the final Bitcoin is mined.

Regardless of what any Ethereum expert or memecoin trader may tell you, the Bitcoin price is the leading indicator of any market shift. If your favorite Telegram group refuses to believe this, take a look at the graphs below tracking crypto’s total market cap and Bitcoin dominance.

While the crypto market saw an increase of 25% in total market cap, Bitcoin dominance has increased by 5%, meaning Bitcoin has done some extremely heavy lifting. In an altcoin market, this trend would be reversed. Bitcoin trending up is a prerequisite for any bull market to begin, and observing price action as the halving next year gets closer will clue you into what we and the market are in store for.

Keep an eye out on Bitcoin’s price as we approach the next halving on 13 April 2024.

AI’s role in the next cryptocurrency narratives

The insane growth and interest in AI took a lot of shine and funding off crypto and poor old Web3. The blockchain industry responded, and has begun integrating the core features of artificial intelligence to enhance crypto-based platforms. Protocols already in the AI domain such as SingularityNET (AGIX), Render (RNDR) or Fetch AI (FET) are booming, with the correct assumption that crypto and AI are extremely complementary.

The metaverse narrative in particular stands to greatly benefit from features such as generative AI, cloud AI solutions, and other tailor-made to take advantage of the blockchain industry.

BlackRock Bitcoin Spot ETF

It’s easy to forget that just a few years ago, when everyone was in profit, mainstream adoption was considered inevitable. For this though, normies like grandma and grandpa would have to be able to own Bitcoin and crypto like a commodity stock without having to remember and safekeep their silly private key or recovery seed. This was thwarted by a variety of bad headlines coming from the crypto space, including the collapse of FTX, rampant scams, and yes, NFT ‘investing’.

BlackRock, one of the world’s largest asset managers with custody of over $9 trillion in assets, has been actively working to create a Bitcoin Spot ETF. Unlike many synthetic assets that simply mirror the price of Bitcoin, the BlackRock ETF would purchase and actively hold Bitcoin. This would offer direct exposure to BlackRock’s customers and likely mean millions of new digital asset investors.

The ETF, unfortunately, relies on approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which has an extensive record of being anti-crypto, but the BlackRock iShares Bitcoin Spot ETF’s chances of approval appears to be a shoo-in, according to most analysts, as are other ETFS from Fidelity, Ark and Grayscale. Its creation would act as a stamp of approval by the US government, and bring TradFi adoption to Bitcoin.

Ethereum rolls out ProtoDanksharding with EIP-4844

Ethereum has been the clear winner for decentralized platforms to conduct fast and secure data transactions. Its massive user base and influence make it the platform for Web3 and decentralized transactions, but there’s still one issue: it’s expensive.

Ethereum has been aware of this issue. In ProtoDanksharding (EIP-4844), on-chain data will be temporarily saved in so-called ‘data blobs’.

Since these data blobs expire in 1-3 months, rather than remaining permanently saved on Ethereum, they cost a fraction as much. Instead of the user paying to maintain the cost of storing this data, that responsibility falls on those using it, such as protocols, exchanges, or indexing services.

These data blobs are expected to be implemented in Q4 2023, followed by Danksharding to dramatically increase the transactions per second (TPS) of the network.

Increased TPS and layer-2 throughput would cement Ethereum as the ideal platform to conduct DeFi transactions, host dApps, and trade ERC-20 tokens without taking out a second mortgage on the family farm.

Improved macro conditions

Central bank interest rates have been steadily increasing since the end of the pandemic, causing investors rush to pile into safer investments, such as US Treasury Bonds, and driving down the value of risk-on assets, including cryptocurrencies.

The poor macro-economic environment is a global consequence of the quantitative easing, or stimulus spending, that occurred during the pandemic, and was quickly followed by inflation. The reverse of easing, quantitative tightening, is currently being wielded to increase interest rates and ring out the excess capital still in the economy to bring inflation back down.

However, governments will eventually have to decide when enough anti-inflation measures have been deployed, or else a recession will begin and further damage the economy. Preston Caldwell, senior economist of the MorningStar Research Services LLC, estimates that rates will begin to be cut in early 2024, claiming that this will be when inflation appears to be returning to the target of 2%.

Honorable Mention: U.S. Elections

There’s been some speculation that Satoshi Nakamoto timed his Halving cycle to coincide with the U.S. election cycle. Politicians are notoriously apprehensive to try anything economically risky that might hurt their voters’ pockets during an election year. With a growing percentage of the population now owning crypto, especially the younger demographic, cryptocurrency regulation will become a very hot issue next year. With candidates such as Robert F. Kennedy, Tulsi Gabbard and Vivek Rawasamy all throwing their weight behind Bitcoin at May’s flagship Bitcoin 2023 Miami conference, expect a muted response from regulators in 2024.

Conclusion

The previous cycle’s objectives were laser-focused on attaining mainstream adoption, onboarding newcomers to crypto and Web3, and demonstrating that digital assets offer substantial advantages to the global economy and traditional banking system.

This time round, a more sophisticated crypto sector, buoyed by the growth of Web3, will show that it’s expanding its reach to TradFi, as well as integrating new technology like AI to offer users leveled-up DeFi and NFT applications for use across the growing digital economy.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

How Do We Ethically “Reitre” Our First Self-Aware AGI Prototypes? | Highlights from Season 1 Finale

What is the price of human creativity?

In a world where LLMs are able to generate ideas for dime a dozen, can humans expect to retain their role in society?

In an era of rapid technological advances, Large Language Models (LLMs), are seen as a frontier pushing the boundaries, especially in the realm of human creativity. LLMs like GPT-4, can generate text that is not only coherent but also creative. This has led some to speculate that such models could soon surpass human ingenuity in generating groundbreaking ideas. Research has found that the average person generates less creative ideas than LLMs, but the best ideas always come from the rare creative humans.

This leads us to one crucial question: “Can AI agents discern what makes an idea good?” Even though they are capable of generating ideas, they cannot (at this time) properly understand the quality of their ideas.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s have a short dive into how AI agents work.

The Mechanics of AI and Language Models

Nobody doubts that artificial intelligence is a game-changer. If you are reading this article, you are on the forefront of the explorers of the effects of this technology, and have probably played with it first-hand.

AI has revolutionized many different industries since the 1950s, when machine learning was first conceptualized. But let’s narrow our focus a bit on the superstars of today, Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and LLaMA. What is it about them that sets them apart?

Most people don’t have the time to learn how to properly work and prompt LLMs. ChatGPT, in particular, opened the floodgates by providing a pre-prompted model that is highly effective at understanding the context of requests and giving its best shot at producing the desired output. GPT was available before, through the OpenAI dashboard and API, but ChatGPT is what made it accessible and thus popular.

Certainly, it has its own issues and quirks, but fundamentally it does a good enough job that it can actually save you time in your work. Up to you if you consider it ethical or not.

So, how do they actually work?

Well, if you’ve been living under a rock, give it a spin at https://chat.openai.com. The free GPT 3.5 version is good enough to give you a demonstration of its capabilities.

These models have been trained on vast sets of text data and they are able to combine, regurgitate, and generate outputs in response to instructions (prompts), sometimes in completely unique ways.

So they can churn out content that appears original, but the kicker is that they don’t understand the value or meaning of the longer forms they themselves generate. You need a human for that. They produce highly legible and contextual outputs, relying on their training analyzing large sets of text and identifying patterns among words. They then use this information to predict what comes next. Models use so-called ‘seeds’: random numbers that make each response unique and varied. This is why it sometimes feels like a hit or miss with prompts that worked one day, but not the next.

The Bottom Line:

Are LLMs a valuable tool for the modern creative worker?

Absolutely.

Are they a replacement for human creativity?

Not by a long shot.

What Makes an Idea Good?

AI models share some similarities with human brains. They both rely on prediction mechanisms to generate outputs. The difference is models predict the next word in a sentence, while humans are trying to predict future outcomes based on the entire flow of an idea. We don’t just blindly generate ideas for the sake of it, although that too happens when we are bored.

Most often, we already have some goal behind our ideas. Whether this is to make money, deal with a specific problem or situation, or decide what kind of outfit and perfume will present us in the best light. These are all goal-oriented endeavors.

Models, on the other hand, are prompt driven – prediction is their only goal. So they do their best to fulfill the criteria of the prompt as they understand it, and predict which words are most likely to be the correct answer.

Fundamentally, defining what is a ‘good idea’ is incredibly difficult. At the moment, only humans decide on which ideas are good for which situation – and we’re not really great at doing that. We’ve all embraced an idea only to generate a terrible result, and vice versa, misjudged ideas that ended up having great outcomes.

So it cannot be the outcome alone that decides the goodness of the idea. Other factors play a role, and are all context-dependent. If you are an artist, originality will dictate what is a good idea. If you are a mother, the safety and wellbeing of your children will play a major role.

Some good ideas are established. They have a brand reputation. For example these would be:

• Going to the dentist regularly

• Not spending all the money you have and investing some of the money you save

• Have enough food to avoid constant trips to the supermarket (or to survive the winter)

• Don’t go outside naked

The conclusion I draw here is that ideas are as good as the context in which they were made. Evaluating any one of them requires great understanding and awareness of the physical, emotional, and mental state of the person that made them, as well as their worldview, knowledge, and desires.

In other words, only you (and sometimes your psychiatrist) could know what a good idea is.

In your experience, what has made an idea good or bad? Is it its impact, its uniqueness, or something else entirely? Share some stories in the comments.

So when we talk about AI generating ideas, it’s not enough to ask if those ideas are new or unique. We must also ask if those ideas are impactful, relevant, and emotionally resonant. Because that’s where AI currently falls short. It simply can’t evaluate these aspects; it just confabulates based on what it’s been trained to do.

AI and Human Creativity: A Symbiotic Relationship

It would be shortsighted to dismiss AI and LLMs as mere tools with zero utility. This is precisely why we don’t see anybody argue that LLMs are useless. In fact, they are great and can do a better job than an average person in some tasks, but they still need at least an average person to be able to do the job. So collaboration is in order.

AI can act as a brainstorming partner, throwing out hundreds of ideas a minute. This ‘idea shotgun’ approach can be invaluable for overcoming creative blocks or for quickly generating multiple solutions to a problem.

Take the instance of the short film Sunspring, written by an AI but directed and performed by humans. The AI provided the raw narrative, but it was the human touch that turned it into something watchable, even if they didn’t edit it at all. This was created seven years ago. The LLMs we have today like ChatGPT would do a much better job. Yet somehow the crew managed to turn it into a compelling story.

Consider musicians who use AI to explore new scales, filmmakers who use it for script suggestions, or designers who employ AI to create myriad design prototypes. They’re not using AI to replace their own creativity, but to augment it.

Here’s the key: the human mind filters these AI-generated ideas, selects the most promising ones, refines them, and brings them to life. In other words, humans provide the ‘why’ and ‘how’ that AI currently lacks. Fundamentally, human creativity is simply priceless.

Why use AI in your creative work?

• Speed: AI can rapidly generate ideas

• Diversity: It can cover a broad spectrum of topics

• Insight: But it lacks the depth of human intuition

• Skill Enhancement: Write better or create unique art (even if you are not an ‘artist’)

Personally, I’m not worried. I see AI as an extension of my creativity. AI can be a powerful ally in our creative endeavors, serving not as a replacement but as an enhancement to human creativity.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

Two Robots Ponder the Ethics of AGI Self Awareness | Highlights from Season 1 Finale

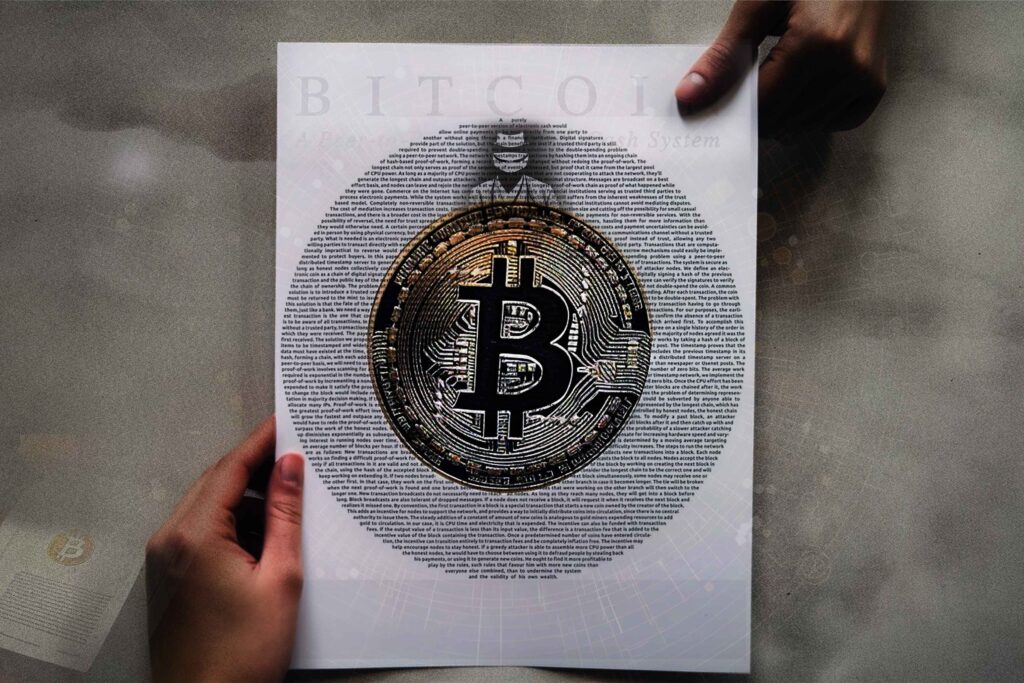

Bitcoin Whitepaper: Satoshi’s Halloween Monster Turns 15

Introduction

A not-so-long time ago, a scary monster was delivered into the world on Halloween by a mysterious inventor, then quickly cast out and pursued by a pitchfork-wielding mob of regular folk that accused it of facilitating the most heinous crimes in a place where regular folk didn’t go: The Dark Web.

I’m of course talking about Bitcoin, not Frankenstein’s deadhead. In both instances, these creatures have proven to be all but unkillable in the best of Halloween traditions. In Bitcoin’s case, the original cryptocurrency has been giving the traditional finance sector, governments, and regulators the heebie-jeebies ever since.

Let’s journey back to explore the genius behind it, and the key concepts that have reshaped the world of finance and technology.

What is the Bitcoin Whitepaper?

The Bitcoin Whitepaper is a concise, nine-page masterpiece written by an enigmatic figure known as Satoshi Nakamoto. Its title, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,” immediately hints at its revolutionary nature. Essentially, it proposes a system for conducting electronic transactions without the need for intermediaries like banks, using a digital currency named Bitcoin (BTC).

Satoshi Nakamoto distributed the Bitcoin Whitepaper on October 31, 2008, to the metzdowd.com mailing list of pioneering cryptography and digital privacy enthusiasts known as cypherpunks. Remarkably, this was a mere 46 days after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, a major event in the global financial crisis. The timing was impeccable, sparking the beginning of a new financial era.

Its ideas laid the foundation for cryptocurrency and blockchain technology and were transformed only 2 months later (3 January 2009’s Bitcoin Genesis Block) into arguably the greatest financial technology innovation that the world has seen. It provided its adopters with the ability to create a decentralized network with a digital currency that was open to all and devoid of intermediaries or geographical borders.

The whitepaper emerged during the global financial crisis of 2008, a time when the public’s trust in traditional financial institutions had been severely eroded, and was inspired by the failure of banks to protect normal investors. Nakamoto’s solution was a system that could operate without reliance on such institutions, providing a secure, trustless, and efficient way to exchange value. It contained revolutionary new concepts and solutions to a problem that has plagued humankind for millennia.

And interestingly enough, it almost sunk without a trace, receiving a very lukewarm response that forced Nakamoto to reprint it again on 3 November 2008. This time, their community noticed, and the rest is history.

When Was the Bitcoin Whitepaper Published?

Who is Satoshi Nakamoto?

The identity of Satoshi Nakamoto remains one of the greatest mysteries in the crypto world. Whether it’s a single individual or a group working under this pseudonym, Nakamoto’s true identity remains unknown.

Despite various claims and speculations, the creator of Bitcoin has chosen to remain in the shadows or is not alive anymore, allowing the cryptocurrency to thrive without a central figure and become a clear commodity instead of a hated security.

The leading candidates range from (deceased/cryogenically frozen) engineer Hal Finney to British programmer Adam Back (according to this documentary) to controversial names like “Fake Satoshi” Craig Wright and incarcerated felon Paul LeRoux. And who can forget poor Dorian Nakamoto?

Significantly, Satoshi used the words “we” and “our” way before they became gender-bending personal pronouns, and this indicates that more than one member of the Cypherpunks was involved. In any case, the Bitcoin Whitepaper is built on ideas that were developed over decades.

Here are a few of the biggest pre-Bitcoin block builders:

• Adam Back’s Hashcash, developed in 1997, influenced Bitcoin’s proof-of-work system by introducing the idea of using computing power as a security measure.

• Nick Szabo’s Bit Gold proposal in 1998, although never implemented, shared similarities with Bitcoin, including the use of proof-of-work and decentralized timestamped transactions.

• Wei Dai’s b-money, also from 1998, contributed ideas like community verification and recording of transactions, a cornerstone of Bitcoin’s decentralized network.

• Hal Finney’s Reusable Proof of Work (RPOW) in 2004 demonstrated the secure transfer and exchange of digital tokens without a central authority, aligning with Bitcoin’s core principles.

These pioneers contributed a Lego set of ideas and intellectual property that Satoshi deconstructed and remolded to create Bitcoin. Which was a perfect expression of the cypherpunk movement that uses open-source collaboration to continue to shape cryptocurrency innovation today in arenas as diverse as Web3, DeFi, Crypto AI, and Ethereum’s evolution.

Bitcoin Whitepaper: Core Concepts To Know

What is the double-spending problem?

At the heart of the Bitcoin Whitepaper lies the “double-spending problem.” This challenge arises in digital currency systems when someone attempts to spend the same digital token more than once. How could participants trust without a central intermediary who’s keeping tabs that counterparties did not act maliciously? We need to know that the previous owners did not sign any earlier transactions.

Nakamoto proposed a brilliantly simple but effective mechanism: the network had to be able to announce all transactions publicly and establish a consensus mechanism among network participants. In simple terms, only the first transaction with a specific digital coin is considered valid. This consensus is achieved by publicly broadcasting all transactions on the Bitcoin network, preventing double-spending.

Satoshi’s P2P system for electronic payments requires a distributed network of honest nodes. As long as the honest nodes have more CPU power than bad actors, the system will stay secure and be able to reject fraud. The nodes “vote” with their computer power. A voting system can also be used to govern changes, rule changes and incentives.

Solving the Byzantine Generals’ Dilemma

Though not explicitly mentioned in the whitepaper, the concept of the Byzantine Generals’ Dilemma is crucial to understanding Nakamoto’s blockchain design. It addresses the challenge of achieving consensus among distributed nodes that may be untrustworthy or malicious. Consensus mechanisms like proof-of-work (PoW) are employed to overcome this dilemma.

The Timestamp Server: Creating an Immutable Transaction History

The timestamp server is pivotal in maintaining the integrity of the Bitcoin network. It orders transactions and prevents double-spending by using cryptographic hashes. The use of SHA-256 hashing ensures security and authenticity.

SHA-256: Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit

SHA-256 is a widely used hashing algorithm in Bitcoin. It transforms transaction data into a unique, fixed-length string of 256 bits, providing a digital fingerprint for verification and security.

How do miners timestamp transactions?

Miners play a vital role in the Bitcoin network by competing to solve cryptographic puzzles that are adjusted by an algorithm to become more difficult or easier every 2,016 blocks (about 2 weeks), depending on the number of mining participants. They timestamp blocks and strengthen the validity of previous timestamps, creating a blockchain of transaction data that can be viewed on a public ledger online. This ensures trust and agreement across the network.

Reclaiming Disk Space with Merkle Trees

As a blockchain grows, storage eventually becomes a concern. Nakamoto’s solution involves using Merkle trees to optimize data storage. These trees reduce the space required for historical transactions while maintaining security.

Single Payment Verification (SPV) Wallets

Nakamoto envisioned a decentralized payment network where everyone could store and transfer digital assets securely. Single Payment Verification (SPV) wallets offer a lightweight and efficient way to verify transactions without downloading the entire blockchain. They prioritize convenience and mobility while maintaining trustworthiness.

Conclusion

Whether you consider the crypto sector to be a Ponzi trick or a lucrative treat that will one day pay for your retirement if you can HODL onto it long enough, there’s no denying after reading Satoshi Nakamoto’s whitepaper that it is a work of genius that has irrevocably changed the world of finance and technology through the power of decentralization.

Bitcoin has provided the world population with the ability to create money for the people, by the people, that is immune to centralized intermediary ills like inflation and corruption. What we do with this gift, and who we choose to trust as leaders, is of course up to us. If you look at the plundering and damage done by the likes of North Korea’s Lazarus Group and false prophets like Sam Bankman-Fried and Do Kwon in recent years, there’s still a long way to go.

The beauty of Bitcoin is that it doesn’t require you to trust people, only its code. In just nine pages, it offers elegant solutions to age-old monetary challenges, providing a decentralized, trustless, and secure system for exchanging value.

With Bitcoin, the power shifts from centralized institutions to the people, marking a significant step toward a more equitable financial future.

With 2024 ushering in another Bitcoin Halving and in all likelihood a Bitcoin Spot ETF, the holy grail of crypto milestones,Satoshi’s benevolent monster is only getting started.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)