Steve Fly is a countercultural musician, writer, and gadfly who is incorporating AI into his creative process. He mentioned taking some inspiration from our publisher Ben Goertzel and his ‘Hyperseed-1’ theories so I decided to interview him about how he thinks about it and what he’s doing.

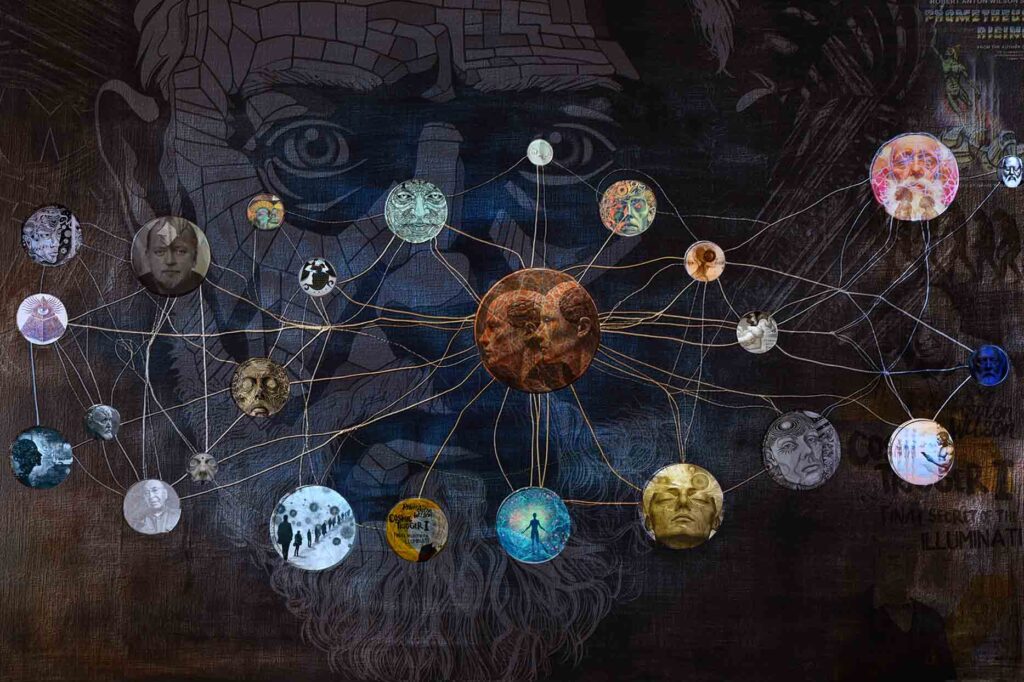

Steve James Pratt, aka Fly Agaric 23, aka Steve Fly has worked and lived as a DJ/turntablist, drummer and poet. He has worked with Indian composer Surinder Sandhu, jam band supergroup Garaj Mahal, and The Gregory James Band (as turntablist). He toured England, the Netherlands, and Germany as a drummer and all-round helper to John Sinclair (RIP), the legendary poet and co-creator of the revolutionary early punk/metal band The MC5. You can find Steve’s full musical biography here. Steve was an associate producer of the 2003 film Maybe Logic, and musical director for the Cosmic Trigger play (2014), performed live at the 26th Annual James Joyce Symposium in Antwerp (2017). He recently performed at the Brainwash Philosophy Conference in Amsterdam (2024). He also makes weird sounds with his mouth. For some background and context, see my (badly) transcribed-by-ear interview with Saul Paul Sirag about some physics principles and structural foundations behind RAW’s Schrödinger’s Cat Trilogy.

Rabbit Holes & Riffs

Mohawk (with John Sinclair)

Schudio – graffiti art gallery

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)