It used to be a bit of a secret in tech circles. But given the recent rise in the social and even political acceptance of psychedelic drug and plant use in the USA and elsewhere, now it can be told. Psychedelics and extreme technological change go together like peanut butter and jelly.

This new book of interviews by David Jay Brown casts a wide net. It chases after what the various interview subjects think about the Singularity, but beyond that, as Brown says in my conversation with him, he asks them about, “Simulation Theory… DMT entities… psychedelics and ecological awareness, God, and death.”

A diverse cast of characters are on the receiving end of Brown’s inquiries, and almost every one of them remarks that Brown really asks the big questions. My personal favorite interviewees include the great trippy graphic novelist/comic book writer and bon vivant Grant Morrison, the writer Erik Davis whose recent book High Weirdness looks at far out psychedelic, sci-fi, techno-visions of the 1970s through the lens of the works of Philip K. Dick, Robert Anton Wilson and Terence McKenna, and the almost indescribable Bruce Damer who seems to be engaged in projects related to almost everything –including space science, virtual reality and the origin of life, just to name a few. Damer also curates the DigiBarn in Santa Cruz, which holds libraries and archives of Timothy Leary and Terence McKenna. These are among the many wildly brilliant interview subjects.

I met David Jay Brown in the mid-1980s, back when I was publishing High Frontiers, a predecessor to Mondo 2000 (as Mindplex is its descendent). Since then I’ve been consistently impressed by his output as a writer and interviewer. He has written for Scientific American, Wired and other periodicals. Books include ‘Mavericks of the Mind’, ‘Conversations on the Edge of the Apocalypse’, ‘The New Science of Psychedelics: At the Nexus of Culture, Consciousness, and Spirituality’ and ‘Women of Visionary Art’.

RU Sirius: What made you decide to combine the themes of psychedelics and the Singularity, and how did you choose the people you would interview?

David Jay Brown: I think the rise in Artificial Intelligence and the psychedelic renaissance are two of the most important forces driving the future evolution of consciousness right now, and that they dovetail in a way that mutually compliments one another. Psychedelics have inspired the development of computer technology and software development from the beginning, and the ecological awareness, personal boundary dissolution, creativity, and spiritual elevation that psychedelics often bring provide an essential balance to the foundational development of AI, its integration into the world, and may assist in reducing the possible dangers that it could bring.

As with all my interview collections, the people that I chose to interview are simply the people whose work are inspiring me, whose books I’ve been reading, and I let it organically grow as I proceed with the project.

Another major theme in the book is about exploring the extended state DMT research and the possibility of non-human entity contact, which I think will also be major factor influencing the future evolution of consciousness, and a number of the people in the collection – such as Andrew Gallimore, David Luke, and Carl Hayden Smith – were chosen for the role that they’re playing in this research and exploration. In addition to contemplating the symbiotic relationship between AI and psychedelics, I see both as catalysts for expanding human potential and pushing the boundaries of what it means to be conscious in the 21st century. AI has the potential to radically transform our cognitive processes, but it needs the human element – the kind of insight that psychedelics offer – to help guide its ethical development and avoid purely mechanistic outcomes. By engaging with these two powerful forces, we’re not only enhancing our technological abilities but also deepening our relationship with the natural world, the cosmos, and the unknown realms of consciousness.

The interviewees were chosen not just for their expertise, but also because they represent a wide spectrum of perspectives – scientific, philosophical, spiritual – on these issues. They are the thought leaders pushing the envelope in their respective fields, and I wanted their diverse voices to reflect the complexity of the Singularity and the transformative role that psychedelics may play in shaping it.

RU: There’s not a lot of Kurzweilian hard-science singularitarianism in the book. How would you respond to that? It’s a very expansive view of the theme (which I like). What versions of singularities do you find most compelling?

DJB: I was corresponding with Ben Goertzel, and he was supposed to be in the collection, but he got too busy as my deadline was approaching and so, unfortunately, he didn’t make it into this book. I interviewed Ray Kurzweil for two of my previous collections, and corresponded with him as I was doing this book as well, but exploring the notion of the Singularity was really only one of the themes in the book, and the title was chosen by my publisher after the book was completed. The notion of the technological Singularity, that Kurzweil and others have popularized, as a reference to the future time when digital electronic minds become more intelligent than all human minds combined – which is a poetic application of the term borrowed from astrophysics, describing the point where the known laws of physics break down, like the center of a Black Hole or whatever state of the universe existed before the Big Bang, and future predictions can’t be made – was a good question to stimulate the imagination of my interviewees.

Other questions that were explored for the same reason had to do with Simulation Theory, the possible reality of the DMT entities, the relationship between psychedelics and ecological awareness, thoughts on the concept of God, and what happens to consciousness after death.

The notion of the Singularity is similar to Terence McKenna’s idea of an attractor or transcendental object at the end of time where novelty becomes infinite, and Teilhard de Chardin’s notion of the Omega Point, the final evolutionary point of unification between God and humanity. It’s a great concept to stimulate our thinking about what could be, during a future time where reality blurs with the imagination. The Singularity, as Kurzweil and others have framed it, often focuses on technological advancements leading to a superintelligence that reshapes our reality, but my approach intentionally opens the door to more speculative, expansive interpretations of this transformative moment. I find versions of the Singularity compelling when they incorporate a sense of mystery, where not just technology but consciousness itself becomes the focal point of evolution. This includes models like McKenna’s timewave theory, where consciousness reaches a crescendo, or de Chardin’s Omega Point, suggesting an inevitable spiritual awakening or divine integration. In these frameworks, the Singularity isn’t just a technological event – it’s a spiritual and philosophical one, where the boundaries between human, machine, and the universe dissolve. The potential for contact with non-human intelligences, whether through DMT or other means, might also play a role in how we conceptualize future consciousness expansion. For me, the most compelling version of the Singularity is one that embraces not only the scientific possibilities but also the profound unknowns of existence.

RU: You wrote “the kind of insight that psychedelics offer – to help guide its ethical development and avoid purely mechanistic outcomes.” I myself have a line in my memoir that psychedelics may be necessary to lubricate an otherwise brittle and mechanistic tech future. But a lot of the high end techies that are into psychedelics like Musk or Thiel seem to develop superman or supremacist ideas and attitudes. When I interviewed Martin Lee about ‘Acid Dreams’ for High Frontiers back in 1987 he said psychedelics can be “exaggerants” that bring out whatever potential is inside a person in an outsized fashion. What do you think about the lessons learned about the unreliability of psychedelic use in turning out enlightened or compassionate humans?

DJB: Yes, “exaggerants” is a good term, and I understand your concern. As Stan Grof points out, psychedelics are non-specific brain amplifiers, and they don’t inherently bring out the positive attributes of people. They amplify what’s already there. I recall hearing stories about Pentagon officials doing acid and dreaming up new mass-killing technologies, and we all know what happened with Charles Manson and his followers. There are many people with sociopathic personalities in positions of great power, and according to Tim Ferriss all of the billionaires that he knows, without exception, are using psychedelics.

But sociopaths only make up 1 to 4 percent of the population. More than 96 percent of human beings, I think, have good intentions, and this gives me great hope as psychedelics awaken the masses. I think that as critical thresholds of positive psychedelic awareness are reached, this will drive compassionate action, ecological awareness, and enlightened conscious evolution. Also, people are complex, and often it’s not black and white as to what’s dark and what’s light, especially as consequences unfold in often unexpected and surprising ways, and I do trust that a higher intelligence inherent in the natural world is helping to guide us in ways that may not be obvious to our rational minds. While psychedelics can certainly amplify darker tendencies in some individuals, particularly those in positions of power or with pre-existing sociopathic traits, I believe the broader cultural awakening that psychedelics foster will lean toward a more compassionate and interconnected world. The key lies in set and setting, as well as in education and integration practices. With responsible use and proper guidance, psychedelics have the potential to help individuals confront their shadows, fostering deep healing and growth. But you’re right – it’s unreliable to assume that psychedelics alone will result in enlightened or compassionate humans.

Transformation requires intention, community support, and ethical frameworks to truly guide individuals toward positive change. In this way, psychedelics are tools, not cures – they provide the potential for insight, but the outcome depends on how that insight is applied.

RU: I loved McKenna and his vision. Back in the High Frontiers days in the mid-1980s, he told us that the interior of the human was going to be externalized, and what we imagine will simply come to be and this was years before everyone was talking about VR. Still, Timewave Zero predicted a massive transformation culminating in December of 2012. Believers will say that the transformation happened under the surface and it’s just not visible, which is what all religionists and cultists say when a prophecy fails. But the Black Mirror reality of today is not something Terence would like. (Terence himself didn’t take the predictions as seriously as others who adapted it)

So the question here is whether you think faith can be excessive and – just as the hyper-rationalists could use some influence from the visionary or spiritual – a lot of psychedelicists could use a dose of rationality.

DJB: I certainly agree that balancing faith and rationality is a good idea, and that too much of either can be excessive. I always viewed Terence as more of a storyteller and a poet than a scientist, and as much as I think many of insights are quite compelling, I take much of what he said with a grain of salt, and you’re right, I don’t think that Terence even took his own predictions that seriously. He actually changed the date for the end of his novelty-accelerating Timewave model a number of times, and December 21st of 2012 was chosen to align with the end of the Mayan calendar, so I see the endpoint that he predicted as more of poetic interpretation of where human evolution is headed – that seems to resonate with what Kurzweil describes as the Singularity, what de Chardin means by the Omega Point, and what Timothy Leary and Robert Anton Wilson mean by the actualization of the 8th brain circuit, which also seem more poetic than scientific.

As for the idea that we are living in ‘Black Mirror’ reality today, I think that this perspective is open to interpretation. Most certainly the dark aspects of the world have been amplified. Those in power have sought greater and greater methods of controlling the human herd, and they now have access to technologies that can seemingly enslave much of humanity. But this tension between enslavement and liberation isn’t really new, it’s just been greatly amplified. We live in a dualistic universe, and I think that there will always be a Yin-Yang balance of dark and light forces. It seems that our species is wobbling on the edge of either planetary suicide or divinity status, and this growing tension has continued to escalate and intensify. But I think it has always seemed this way. In Tim Rayborn’s book ‘A History of the End of the World’, he makes it clear that this inclination toward apocalyptic thinking has been present throughout human history, as has the notion that humanity is on the verge of a Golden Age of Enlightenment. Are we headed toward an environmental apocalypse and global mass extinction, or will our wayward species overcome the immense challenges that currently face us, and become all-powerful and immortal superhuman masters of space and time? These teetering polarized possibilities have now become so extreme that it seems like our species is facing an evolve-or-die intelligence test, but I suspect that it has always seemed this way and will always seem this way in our dualistic universe. I know that many people think that the world has gotten too dark to be optimistic, however, I suggest that we consider that two things may have influenced this perspective regarding optimism and excitement about future possibilities: the acceleration and intensification of both positive and negative forces, as I’ve described, as well as the aging process. Young people seem more optimistic than the older generations. I don’t think the world has just gotten worse; I think it’s gotten both better and worse at the same time, and the aging process tends to decrease neophilia and increase neophobia. This happens in all animal species and humans are no exception. I see all the dystopian possibilities that everyone else my age sees – the division in our country, the climate crisis, the rise of racism, the threat of nuclear war, etc. – but I also see enormous positive potential as well – the psychedelic revolution raising ecological awareness, AI evolution promising advances in medicine and virtually every field of human endeavor, incredible scientific advances, astonishing new technologies, and young people seeing through the corruption in our two-party political system. I suspect that this Yin-Yang nature of world will continue to accelerate and intensify, but that utopia or dystopia will never fully arrive. It will always be some weird mix of the two, with infinite evidence to suggest that either light or dark perspectives will prevail.

I also think that part of the appeal of Terence’s ideas, and the broader psychedelic movement, is the invitation to engage with uncertainty and paradox. The poetic, visionary nature of his predictions encouraged people to look beyond rigid frameworks of understanding, allowing them to imagine and co-create potential futures. But as with all visionary insights, it’s essential to temper them with discernment. Faith can become excessive when it blinds us to reality, just as rationality can become constricting when it limits our capacity for awe and wonder. Psychedelicists, like everyone else, benefit from balancing intuition with logic, especially as the stakes grow higher. In today’s world, where technologies like AI and VR blur the line between imagination and reality, it’s more important than ever to remain grounded while exploring new possibilities. As the collective tension increases, so too does the responsibility on each of us to use our tools – whether technological or visionary – wisely.

In a sense, our challenge is to prevent the ‘Black Mirror’ reality from consuming us, while still allowing space for the unprecedented opportunities of this evolutionary moment. After all, if we can harmonize the rational and the visionary, perhaps we can transcend the dualistic cycles of history and consciously shape a more balanced, compassionate future.

RU: Why DMT? In other words, of all the psychedelics, and there are many of these chemical and plant wonders, what is it about DMT that fascinates us in this accelerating time? What are your thoughts?

DJB: There are several reasons why DMT is special and unique in the world of psychedelics, as well as profoundly relevant to our accelerating time of information overload. Let me first provide a little background on DMT. DMT is endogenous to the human body, it’s found in all mammalian species, and throughout the plant world. It’s ubiquitous throughout nature, and no biochemist can tell you what function it serves in any of these places. It seems to be both a neurotransmitter and a hormone in the human body, but no one really has a clue as to why it’s there. It’s a very simple molecule, derived from the essential amino acid tryptophan, and its place in the natural world is a profound mystery.

In studies with rodents, we know that DMT levels escalate in their brains after cardiac arrest, which lends credence to the popular idea that it mediates the near-death experience in human beings. When ingested in sufficient quantities, DMT experiences generally become an order of magnitude more intense than that of any of the other psychedelics, and it quite literally transports one to another world, which is commonly referred to as “hyperspace” by the psychonauts who have traveled there. One becomes completely immersed in a multi-dimensional reality that completely replaces our three-dimensional world, and it is often reported as seeming “more real than real”. It doesn’t appear to be a hallucination; it seems completely real and one remains fully lucid during the experience. And most profoundly, this new world appears to be populated by hyper-intelligent, non-human entities that seem to take great interest in communicating with us in various ways.

Surprisingly, there is an incredible amount of similarity among the reports from psychonauts as to what these beings look like and how they act towards us. This phenomenon provides the basis for my latest book, ‘The Illustrated Field Guide to DMT Entities’, which is an attempt to create a taxonomy of these beings, and was just published by Inner Traditions.

In the book I describe 25 of the commonly encountered DMT entities – such as gray aliens, jesters, reptilians, octopoid beings, and “the self-transforming machine elves,” that McKenna famously refers to – and Sara Phinn Huntley, Alex Grey, Luke Brown, Harry Pack, and other brilliant artists illustrate them.

This phenomenon is being taken seriously by a number of prestigious scientists – such as Rick Strassman, Andrew Gallimore, and David Luke – who have organized studies at Imperial College in London and elsewhere to put people into extended-state DMT sessions. This is being done with the intention of sending DMT voyagers into longer periods where they can access hyperspace and communicate with these strange entities, to see if there truly is an objective reality to them, and what can be learned from them. In my book ‘Psychedelics and the Coming Singularity’, I interview Gallimore and Luke at length about this phenomenon, as well as Carl Hayden Smith, who is one of the brave subjects in the Imperial College extended-state DMT studies that are currently underway. I think this is some of the most exciting scientific research in human history, as we appear to be building technologies that allow us to consistently and reliably communicate with more advanced species – like the contact with alien beings that has been long-anticipated in our science fiction stories – and this is eerily resonant with the recently leaked Pentagon footage of UAPs, and the reports of secret government programs that some military insiders claim exist with the goal of reverse-engineering the technology of crashed alien vehicles.

But what I’m describing is largely from a Western perspective, as many indigenous peoples in the Amazon basin, who have been using a DMT-based jungle brew known as ayahuasca since prehistory, have long reported contact with powerful spirits and advanced beings during their shamanic journeys. To them, this isn’t news at all, but we’re discovering this at a new technological level, which may provide a more sophisticated medium for communication with these advanced beings. Remember, it was McKenna who first began popularizing DMT back in the 1980s and 1990s, and it was basically an obscure drug at the time. We were just talking about how McKenna predicted that novelty would accelerate with his Timewave model as we evolved – well, he accurately predicted the explosion of interest in DMT that resonates with the explosion of information and novelty that we are presently experiencing.

Another aspect that makes DMT so compelling is its potential to challenge our understanding of reality itself. The fact that so many people report similar experiences, with recurring motifs and entities, raises the question of whether DMT provides access to a shared, objective dimension that exists independently of our usual perception. This idea blurs the line between the subjective and the objective, and it forces us to reconsider the nature of consciousness. Is DMT merely unlocking hidden aspects of our minds, or is it truly opening a doorway to other worlds? These are questions that challenge the core of our scientific and philosophical paradigms. Additionally, in the context of our rapidly accelerating technological world, where we are exploring artificial intelligence and virtual realities, the DMT experience stands out as a reminder that there may be even more advanced, mysterious layers to existence than we can currently fathom. It’s as if DMT serves as a bridge between the ancient wisdom of indigenous practices and the cutting-edge frontiers of modern science.

RU: Is there anything you would like to tell the Mindplex readers about what they might learn or gain in perspective from reading this book?

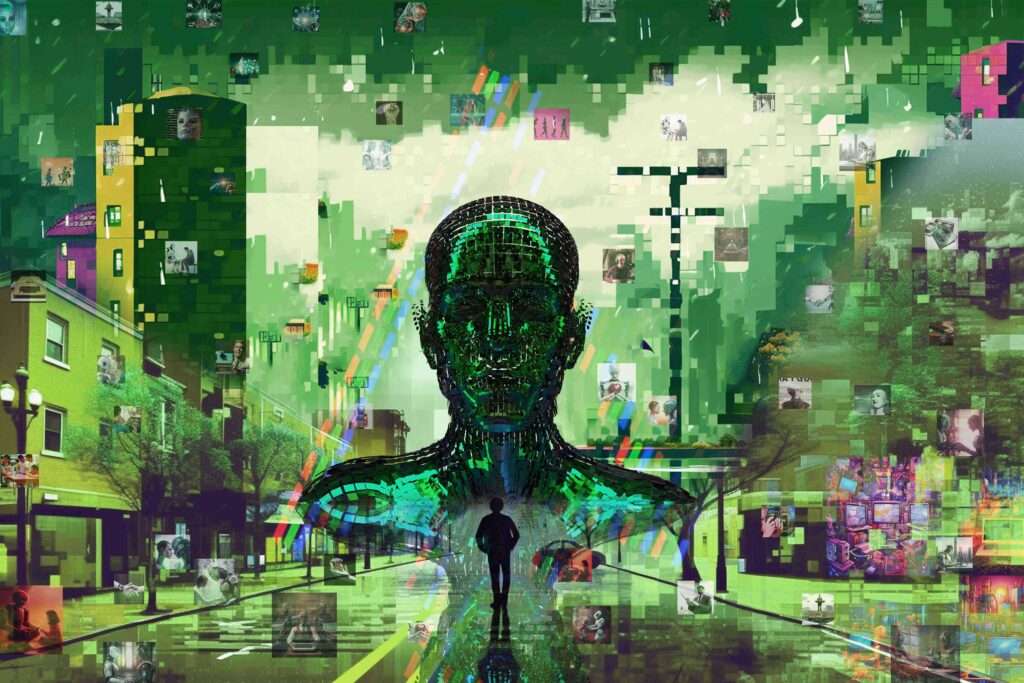

DJB: We’re currently facing a unique juncture in our evolutionary journey, where the human adventure can branch into a multitude of new directions. It’s an extraordinary time that’s filled with great peril and much promise. Never before in human history have so many human minds been interconnected at the speed of light, thanks to the Internet and other evolving electronic communication technologies. All of human knowledge is now available to everyone nearly instantly, and our collective intelligence has been elevated substantially – yet our collective stupidity paradoxically threatens our very existence. I suspect that this ability and interconnection is greatly amplifying human potential and this gives me enormous hope, but there is also much at stake and we could be on the verge of our own extinction.

In my book I bring together the perspectives and ideas from some of the most brilliant minds and far-sighted visionaries on the planet to help us navigate through these difficult times and offer out-of-the-box solutions to some of our most pressing problems. These genius luminaries not only offer hope for our wayward world, but also an excitement about the future that rekindles the optimistic enthusiasm that many of us had back in the 1990s, when ‘Mondo 2000’ magazine saw its heyday, and the future seemed bright and filled with great promise – when the internet, transhumanism, virtual reality, brain technologies, and psychedelics were viewed as fantastic agents of liberation, mind expansion, and evolutionary catalysts, instead of as dark tools of oppression, consumerism, slavery, and control.

By reading ‘Psychedelics and the Coming Singularity’, I hope that people will gain not only a deeper understanding of these transformative forces but also a renewed sense of agency and responsibility. The world may feel chaotic and uncertain, but within this turbulence lies the potential for radical positive change. Through the wisdom and insights of the great thinkers featured in this book, I believe readers will come to see that we are not passive participants in this unfolding story. Rather, we have the power to consciously shape the future and co-create a reality that aligns with our highest aspirations.

Ultimately, this book invites readers to embrace both the mysteries and challenges of this pivotal moment, and to step boldly into the unknown with curiosity, courage, and a sense of hope for what’s to come.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)