More things in heaven and earth

As humans, we tend to compare other intelligences to our own, human, intelligence. That’s an understandable bias, but it could be disastrous.

Rather than our analysis being human-bound, we need to heed the words of Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy.

More recent writers, in effect amplifying Shakespeare’s warning, have enthralled us with their depictions of numerous creatures with bewildering mental attributes. The pages of science fiction can, indeed, stretch our imagination in remarkable ways. But these narratives are easy to dismiss as being “just” science fiction.

That’s why my own narrative, in this article, circles back to an analysis that featured in my previous Mindplex article, Bursting out of confinement. The analysis in question is the famous – or should I say infamous – “Simulation Argument”. The Simulation Argument raises some disturbing possibilities about non-human intelligence. Many critics try to dismiss these possibilities – waving them away as “pseudoscience” or, again, as “just science fiction” – but they’re being overly hasty. My conclusion is that, as we collectively decide how to design next generation AI systems, we ought to carefully ponder these possibilities.

In short, what we need to contemplate is the astonishing vastness of the space of all possible minds. These minds vary in unfathomable ways not only in how they think but also in what they think about and care about.

Hamlet’s warning can be restated:

There are more types of superintelligence in mind space, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy.

By the way, don’t worry if you’ve not yet read my previous Mindplex article. Whilst these two articles add up to a larger picture, they are independent of each other.

How alien?

As I said: we humans tend to compare other intelligences to our own, human, intelligence. Therefore, we tend to expect that AI superintelligence, when it emerges, will sit on some broad spectrum that extends from the intelligence of amoebae and ants through that of mice and monkeys to that of humans and beyond.

When pushed, we may concede that AI superintelligence is likely to have some characteristics we would describe as alien.

In a simple equation, overall human intelligence (HI) might be viewed as a combination of multiple different kinds of intelligence (I1, I2, …), such as spatial intelligence, musical intelligence, mathematical intelligence, linguistic intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, and so on:

HI = I1 + I2 + … + In

In that conception, AI superintelligence (ASI) is a compound magnification (m1, m2, …) of these various capabilities, with a bit of “alien extra” (X) tacked on at the end:

ASI = m1*I1 + m2*I2 + … + mn*In + X

What’s at issue is whether the ASI is dominated by the first terms in this expression, or by the unknown X present at the end.

Whether some form of humans will thrive in a coexistence with ASI will depend on how alien that superintelligence is.

Perhaps the ASI will provide a safe, secure environment, in which we humans can carry out our human activities to our hearts’ content. Perhaps the ASI will augment us, uplift us, or even allow us to merge with it, so that we retain what we see as the best of our current human characteristics, whilst leaving behind various unfortunate hangovers from our prior evolutionary trajectory. But that all depends on factors that it’s challenging to assess:

- How much “common cause” the ASI will feel toward humans

- Whether any initial feeling of common cause will dissipate as the ASI self-improves

- To what extent new X factors could alter considerations in ways that we have not begun to consider.

Four responses to the X possibility

Our inability to foresee the implications of unknowable new ‘X’ capabilities in ASI should make us pause for thought. That inability was what prompted author and mathematics professor Vernor Vinge to develop in 1983 his version of the notion of “Singularity”. To summarize what I covered in more detail in a previous Mindplex article, “Untangling the confusion”, Vinge predicted that a new world was about to emerge that “will pass far beyond our understanding”:

We are at the point of accelerating the evolution of intelligence itself… We will soon create intelligences greater than our own. When this happens, human history will have reached a kind of singularity, an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space-time at the center of a black hole, and the world will pass far beyond our understanding. This singularity, I believe, already haunts a number of science fiction writers. It makes realistic extrapolation to an interstellar future impossible.

Reactions to this potential unpredictability can be split into four groups of thought:

- Dismissal: A denial of the possibility of ASI. Thankfully, this reaction has become much less common recently.

- Fatalism: Since we cannot anticipate what surprise new ‘X’ features may be possessed by an ASI, it’s a waste of time to speculate about them or to worry about them. What will be, will be. Who are we humans to think we can subvert the next step in cosmic evolution?

- Optimism: There’s no point in being overcome with doom and gloom. Let’s convince ourselves to feel lucky. Humanity has had a good run so far, and if we extrapolate that history beyond the singularity, we can hope to have an even better run in the future.

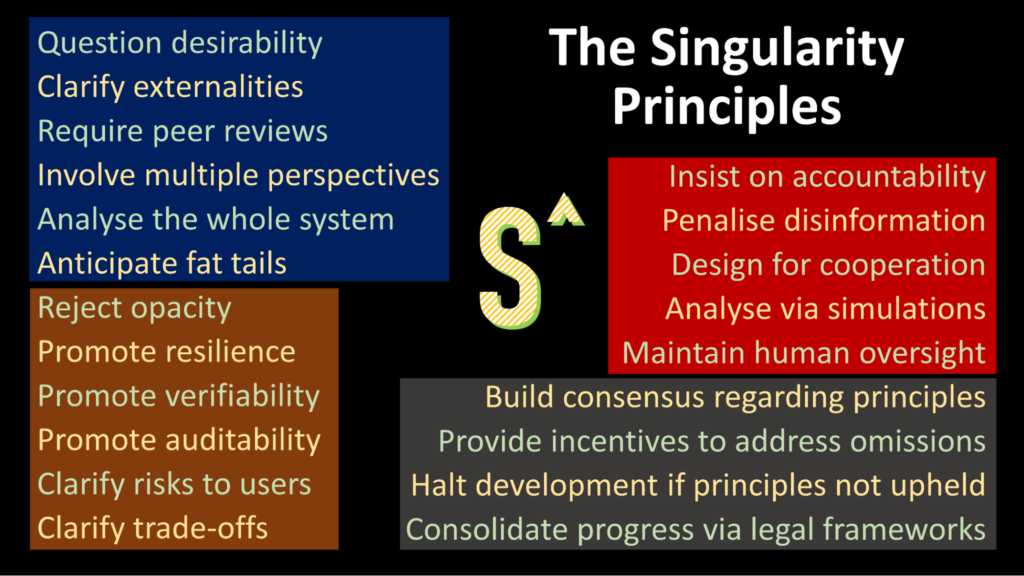

- Activism: Rather than rolling the dice, we should proactively alter the environment in which new generations of AI are being developed, to reduce the risks of any surprise ‘X’ features emerging that would overwhelm our abilities to retain control.

I place myself squarely in the activist camp, and I’m happy to adopt the description of “Singularity Activist”.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean I’m blind to the potential huge upsides to beneficial ASI. It’s just that I’m aware, as well, of major risks en route to that potential future.

A journey through a complicated landscape

As an analogy, consider a journey through a complicated landscape:

In this journey, we see a wonderful existential opportunity ahead – a lush valley, fertile lands, and gleaming mountain peaks soaring upward to a transcendent realm. But in front of that opportunity is a river of uncertainty, bordered by a swamp of ambiguity, perhaps occupied by hungry predators lurking in shadows.

Are there just two options?

- We are intimidated by the possible dangers ahead, and decide not to travel any further

- We fixate on the gleaming mountain peaks, and rush on regardless, belittling anyone who warns of piranhas, treacherous river currents, alligators, potential mud slides, and so on

Isn’t there a third option? To take the time to gain a better understanding of the lie of the land ahead. Perhaps there’s a spot, to one side, where it will be easier to cross the river. A location where a stable bridge can be built. Perhaps we could even build a helicopter that can assist us over the strongest currents…

It’s the same with the landscape of our journey towards the sustainable superabundance that could be achieved, with the assistance of advanced AI, provided we act wisely. That’s the vision of Singularity Activism.

Obstacles to Singularity Activism

The Singularity Activist outlook faces two main obstacles.

The first obstacle is the perception that there’s nothing we humans can usefully do, to meaningfully alter the course of development of ASI. If we slow down our own efforts, in order to apply more resources in the short term on questions of safety and reliability, it just makes it more likely that another group of people – probably people with fewer moral qualms than us – will rush ahead and create ASI.

In this line of thinking, the best way forward is to create prototype ASI systems as soon as possible, and then to use these systems to help design and evolve better ASI systems, so that everyone can benefit from what will hopefully be a wonderful outcome.

The second obstacle is the perception that there’s nothing we humans particularly need to do, to avoid the risks of adverse outcomes, since these risks are pretty small in any case. Just as we don’t over-agonise about the risks of us being struck by debris falling from an overhead airplane, we shouldn’t over-agonise about the risks of bad consequences of ASI.

But on this occasion, where I want to focus is assessing the scale and magnitude of the risk that we are facing, if we move forward with overconfidence and inattention. That is, I want to challenge the second of the above misperceptions.

As a step toward that conclusion, it’s time to bring an ally to the table. That ally is the Simulation Argument. Buckle up!

Are we simulated?

The Simulation Argument puts a particular hypothesis on the table, known as the Simulation Hypothesis. That hypothesis proposes that we humans are mistaken about the ultimate nature of reality. What we consider to be “reality” is, in this hypothesis, a simulated (virtual) world, designed and operated by “simulators” who exist outside what we consider the entire universe.

It’s similar to interactions inside a computer game. As humans play these games, they encounter challenges and puzzles that need to be solved. Some of these challenges involve agents (characters) within the game – agents which appear to have some elements of autonomy and intelligence. These agents have been programmed into the game by the game’s designers. Depending on the type of game, the greater the intelligence of the built-in agents, the more enjoyable it is to play it.

Games are only one example of simulation. We can also consider simulations created as a kind of experiment. In this case, a designer may be motivated by curiosity: They may want to find out what would happen if such-and-such initial conditions were created. For example, if Archduke Ferdinand had escaped assassination in Sarajevo in June 1914, would the European powers still have blundered into something akin to World War One? Again, such simulations could contain numerous intelligent agents – potentially (as in the example just mentioned) many millions of such agents.

Consider reality from the point of view of such an agent. What these agents perceive inside their simulation is far from being the entirety of the universe as is known to the humans who operate the simulation. The laws of cause-and-effect within the simulation could deviate from the laws applicable in the outside world. Some events in the simulation that lack any explanation inside that world may be straightforwardly explained from the outside perspective: the human operator made such-and-such a decision, or altered a setting, or – in an extreme case – decided to reset or terminate the simulation. In other words, what is bewildering to the agent may make good sense to the author(s) of the simulation.

Now suppose that, as such agents become more intelligent, they also become self-aware. That brings us to the crux question: how can we know whether we humans are, likewise, agents in a simulation whose designers and operators exist beyond our direct perception? For example, we might be part of a simulation of world history in which Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo in June 1914. Or we might be part of a simulation whose purpose far exceeds our own comprehension.

Indeed, if the human creative capability (HCC) to create simulations is expressed as a sum of different creative capabilities (CC1, CC2, …),

HCC = CC1 + CC2 + … + CCn

then the creative capability of a hypothetical superhuman simulation designer (SCC) might be expressed as a compound magnification (m1, m2, …) of these various capabilities, with a bit of “alien extra” (X) tacked on at the end:

SCC = m1*CC1 + m2*CC2 + … + mn*CCn + X

Weighing the numbers

Before assessing the possible scale and implications of the ‘X’ factor in that equation, there’s another set of numbers to consider. These numbers attempt to weigh up the distribution of self-aware intelligent agents. What proportion of that total set of agents are simulated, compared to those that are in “base reality”?

If we’re just counting intelligences, the conclusion is easy. Assuming there is no catastrophe that upends the progress of technology, then, over the course of all of history, there will likely be vastly more artificial (simulated) intelligences than beings who have base (non-simulated) intelligences. That’s because computing hardware is becoming more powerful and widespread.

There are already more “intelligent things” than humans connected to the Internet: the analysis firm Statista estimates that, in 2023, the first of these numbers is 15.14 billion, which is almost triple the second number (5.07 billion). In 2023, most of these “intelligent things” have intelligence far shallower than that of humans, but as time progresses, more and more intelligent agents of various sorts will be created. That’s thanks to ongoing exponential improvements in the capabilities of hardware, networks, software, and data analysis.

Therefore, if an intelligence could be selected at random, from the set of all such intelligences, the likelihood is that it would be an artificial intelligence.

The Simulation Argument takes these considerations one step further. Rather than just selecting an intelligence at random, what if we consider selecting a self-aware conscious intelligence at random. Given the vast numbers of agents that are operating inside vast numbers of simulations, now or in the future, the likelihood is that a simulated agent has been selected. In other words, we – you and I – observing ourselves to be self-aware and intelligent, should conclude that it’s likely we ourselves are simulated.

Thus the conclusion of the Simulation Argument is that we should take the Simulation Hypothesis seriously. To be clear, that hypothesis isn’t the only possible legitimate response to the argument. Two other responses are to deny two of the assumptions that I mentioned when building the argument:

- The assumption that technology will continue to progress, to the point where simulated intelligences vastly exceed non-simulated intelligences

- The assumption that the agents in these simulations will be not just intelligent but also conscious and self-aware.

Objections and counters

Friends who are sympathetic to most of my arguments sometimes turn frosty when I raise the topic of the Simulation Hypothesis. It clearly makes people uncomfortable.

In their state of discomfort, critics of the argument can raise a number of objections. For example, they complain that the argument is entirely metaphysical, not having any actual consequences for how we live our lives. There’s no way to test it, the objection runs. As such, it’s unscientific.

As someone who spent four years of my life (1982-1986) in the History and Philosophy of Science department in Cambridge, I am unconvinced by these criticisms. Science has a history of theories moving from non-testable to testable. The physicist Ernst Mach was famously hostile to the hypothesis that atoms exist. He declared his disbelief in atoms in a public auditorium in Vienna in 1897: “I don’t believe that atoms exist”. There was no point in speculating about the existence of things that could not be directly observed, he asserted. Later in his life, Mach likewise complained about the scientific value of Einstein’s theory of relativity:

I can accept the theory of relativity as little as I can accept the existence of atoms and other such dogma.

Intellectual heirs of Mach in the behaviorist school of psychology fought similar battles against the value of notions of mental states. According to experimentalists like John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, people’s introspections of their own mental condition had no scientific merit. Far better, they said, to concentrate on what could be observed externally, rather than on metaphysical inferences about hypothetical minds.

As it happened, the theories of atoms, of special relativity, and of internal mental states, all gave rise in due course to important experimental investigations, which improved the ability of scientists to make predictions and to alter the course of events.

It may well be the same with the Simulation Hypothesis. There are already suggestions of experiments that might be carried out to distinguish between possible modes of simulation. Just because a theory is accused of being “metaphysical”, it doesn’t follow that no good science can arise from it.

A different set of objections to the Simulation Argument gets hung up on tortuous debates over the mathematics of probabilities. (For additional confusion, questions of infinities can be mixed in too.) Allegedly, because we cannot meaningfully measure these probabilities, the whole argument makes no sense.

However, the Simulation Argument makes only minimal appeal to theories of mathematics. It simply points out that there are likely to be many more simulated intelligences than non-simulated intelligences.

Well, critics sometimes respond, it must therefore be the case that simulated intelligences can never be self-aware. They ask, with some derision, whoever imagined that silicon could become conscious? There must be some critical aspect of biological brains which cannot be duplicated in artificial minds. And in that case, the fact that we are self-aware would lead us to conclude we are not simulated.

To me, that’s far too hasty an answer. It’s true that the topics of self-awareness and consciousness are more controversial than the topic of intelligence. It is doubtless true that at least some artificial minds will lack conscious self-awareness. But if evolution has bestowed conscious self-awareness on intelligent creatures, we should be wary of declaring that property to provide no assistance to these creatures. Such a conclusion would be similar to declaring that sleep is for losers, despite the ubiquity of sleep in mammalian evolution.

If evolution has given us sleep, we should be open to the possibility that it has positive side-effects for our health. (It does!) Likewise, if evolution has given us conscious self-awareness, we should be open to the idea that creatures benefit from that characteristic. Simulators, therefore, may well be tempted to engineer a corresponding attribute into the agents they create. And if it turns out that specific physical features of the biological brain need to be copied into the simulation hardware, to enable conscious self-awareness, so be it.

The repugnant conclusion

When an argument faces so much criticism, yet the criticisms fail to stand up to scrutiny, it’s often a sign that something else is happening behind the scenes.

Here’s what I think is happening with the Simulation Argument. If we accept the Simulation Hypothesis, it means we have to accept a morally repugnant conclusion about the simulators that have created us. Namely, these simulators give no sign of caring about all the terrible suffering experienced by the agents inside the simulation.

Yes, some agents have good lives, but very many others have dismal fates. The thought that a simulator would countenance all this suffering is daunting.

Of course, this is the age-old “problem of evil”, well known in the philosophy of religion. Why would an all-good all-knowing all-powerful deity allow so many terrible things to happen to so many humans over the course of history? It doesn’t make sense. That’s one reason why many people have turned their back on any religious faith that implies a supposedly all-good all-knowing all-powerful deity.

Needless to say, religious faith persists, with the protection of one or more of the following rationales:

- We humans aren’t entitled to use our limited appreciation of good vs. evil to cast judgment on what actions an all-good deity should take

- We humans shouldn’t rely on our limited intellects to try to fathom the “mysterious ways” in which a deity operates

- Perhaps the deity isn’t all-powerful after all, in the sense that there are constraints beyond human appreciation in what the deity can accomplish.

Occasionally, yet another idea is added to the mix:

- A benevolent deity needs to coexist with an evil antagonist, such as a “satan” or other primeval prince of darkness.

Against such rationalizations, the spirit of the enlightenment offers a different, more hopeful analysis:

- Whichever forces gave rise to the universe, they have no conscious concern for human wellbeing

- Although human intellects run up against cognitive limitations, we can, and should, seek to improve our understanding of how the universe operates, and of the preconditions for human flourishing

- Although it is challenging when different moral frameworks clash, or when individual moral frameworks fail to provide clear guidelines, we can, and should, seek to establish wide agreement on which kinds of human actions to applaud and encourage, and which to oppose and forbid

- Rather than us being the playthings of angels and demons, the future of humanity is in our own hands.

However, if we follow the Simulation Argument, we are confronted by what seems to be a throwback to a more superstitious era:

- We may owe our existence to actions by beings beyond our comprehension

- These beings demonstrate little affinity for the kinds of moral values we treasure

- We might comfort each other with the claim that “[whilst] the arc of the moral universe is long, … it bends toward justice”, but we have no solid evidence in favor of that optimism, and plenty of evidence that good people are laid to waste as life proceeds.

If the Simulation Argument leads us to such conclusions, it’s little surprise that people seek to oppose it.

However, just because we dislike a conclusion, that doesn’t entitle us to assume that it’s false. Rather, it behooves us to consider how we might adjust our plans in the light of that conclusion possibly being true.

The vastness of ethical possibilities

If you disliked the previous section, you may dislike this next part even more strongly. But I urge you to put your skepticism on hold, for a while, and bear with me.

The Simulation Argument suggests that beings who are extremely powerful and extremely intelligent – beings capable of creating a universe-scale simulation in which we exist – may have an ethical framework that is very different from ones we fondly hope would be possessed by all-powerful all-knowing beings.

It’s not that their ethical concerns exceed our own. It’s that they differ in fundamental ways from what we might predict.

I’ll return, for a third and final time, to a pair of equations. If overall human ethical concerns (HEC) is a sum of different ethical considerations (EC1, EC2, …),

HEC = EC1 + EC2 + … + ECn

then the set of ethical concerns of a hypothetical superhuman simulation designer (SEC) needs to include not only a compound magnification (m1, m2, …) of these various human concerns, but also an unquantifiable “alien extra” (X) portion:

SEC = m1*EC1 + m2*EC2 + … + mn*ECn + X

In some views, ethical principles exist as brute facts of the universe: “do not kill”, “do not tell untruths”, “treat everyone fairly”, and so on. Even though we may from time to time fail to live up to these principles, that doesn’t detract from the fundamental nature of these principles.

But from an alternative perspective, ethical principles have pragmatic justifications. A world in which people usually don’t kill each other is better on the whole, for everyone, than a world in which people attack and kill each other more often. It’s the same with telling the truth, and with treating each other fairly.

In this view, ethical principles derive from empirical observations:

- Various measures of individual self-control (such as avoiding gluttony or envy) result in the individual being healthier and happier (physically or psychologically)

- Various measures of social self-control likewise create a society with healthier, happier people – these are measures where individuals all agree to give up various freedoms (for example, the freedom to cheat whenever we think we might get away with it), on the understanding that everyone else will restrain themselves in a similar way

- Vigorous attestations of our beliefs in the importance of these ethical principles signal to others that we can be trusted and are therefore reliable allies or partners.

Therefore, our choice of ethical principles depends on facts:

- Facts about our individual makeup

- Facts about the kinds of partnerships and alliances that are likely to be important for our wellbeing.

For beings with radically different individual makeup – radically different capabilities, attributes, and dependencies – we should not be surprised if a radically different set of ethical principles makes better sense to them.

Accordingly, such beings might not care if humans experience great suffering. On account of their various superpowers, they may have no dependency on us – except, perhaps, for an interest in seeing how we respond to various challenges or circumstances.

Collaboration: for and against

One more objection deserves attention. This is the objection that collaboration is among the highest of human ethical considerations. We are stronger together, rather than when we are competing in a Hobbesian state of permanent all-out conflict. Accordingly, surely a superintelligent being will want to collaborate with humans?

For example, an ASI (artificial superintelligence) may be dependent on humans to operate the electricity network on which the computers powering the ASI depend. Or the human corpus of knowledge may be needed as the ASI’s training data. Or reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) may play a critical role in the ASI gaining a deeper understanding.

This objection can be stated in a more general form: superintelligence is bound to lead to superethics, meaning that the wellbeing of an ASI is inextricably linked to the wellbeing of the creatures who create and coexist with the ASI, namely the members of the human species.

However, any dependency by the ASI upon what humans produce is likely to be only short term. As the ASI becomes more capable, it will be able, for example, to operate an electrical supply network without any involvement from humans.

This attainment of independence may well prompt the ASI to reevaluate how much it cares about us.

In a different scenario, the ASI may be dependent on only a small number of humans, who have ruthlessly pushed themselves into that pivotal position. These rogue humans are no longer dependent on the rest of the human population, and may revise their ethical framework accordingly. Instead of humanity as a whole coexisting with a friendly ASI, the partnership may switch to something much narrower.

We might not like these eventualities, but no amount of appealing to the giants of moral philosophy will help us out here. The ASI will make its own decisions, whether or not we approve.

It’s similar to how we regard any growth of cancerous cells within our body. We won’t be interested in any appeal to “collaborate with the cancer”, in which the cancer continues along its growth trajectory. Instead of a partnership, we’re understandably interested in diminishing the potential of that cancer. That’s another reminder, if we need it, that there’s no fundamental primacy to the idea of collaboration. And if an ASI decides that humanity is like a cancer in the universe, we shouldn’t expect it to look on us favorably.

Intelligence without consciousness

I like to think that if I, personally, had the chance to bring into existence a simulation that would be an exact replica of human history, I would decline. Instead, I would look long and hard for a way to create a simulation without the huge amounts of unbearable suffering that has characterized human history.

But what if I wanted to check an assumption about alternative historical possibilities – such as the possibility to avoid World War One? Would it be possible to create a simulation in which the simulated humans were intelligent but not conscious? In that case, whilst the simulated humans would often emit piercing howls of grief, no genuine emotions would be involved. It would just be a veneer of emotions.

That line of thinking can be taken further. Maybe we are living in a simulation, but the simulators have arranged matters so that only a small number of people have consciousness alongside their intelligence. In this hypothesis, vast numbers of people are what are known as “philosophical zombies”.

That’s a possible solution to the problem of evil, but one that is unsettling. It removes the objection that the simulators are heartless, since the only people who are conscious are those whose lives are overall positive. But what’s unsettling about it is the suggestion that large numbers of people are fundamentally different from how they appear – namely, they appear to be conscious, and indeed claim to be conscious, but that is an illusion. Whether that’s even possible isn’t something where I hold strong opinions.

My solution to the Simulation Argument

Despite this uncertainty, I’ve set the scene for my own preferred response to the Simulation Argument.

In this solution, the overwhelming majority of self-aware intelligent agents that see the world roughly as we see it are in non-simulated (base) reality – which is the opposite of what the Simulation Argument claims. The reason is that potential simulators will avoid creating simulations in which large numbers of conscious self-aware agents experience great suffering. Instead, they will restrict themselves to creating simulations:

- In which all self-aware agents have an overwhelmingly positive experience

- Which are devoid of self-aware intelligent agents in all other cases.

I recognise, however, that I am projecting a set of human ethical considerations which I personally admire – the imperative to avoid conscious beings experiencing overwhelming suffering – into the minds of alien creatures that I have no right to imagine that I can understand. Accordingly, my conclusion is tentative. It will remain tentative until such time as I might gain a richer understanding – for example, if an ASI sits me down and shares with me a much superior explanation of “life, the universe, and everything”.

Superintelligence without consciousness

It’s understandable that readers will eventually shrug and say to themselves, we don’t have enough information to reach any firm decisions about possible simulators of our universe.

What I hope will not happen, however, is if people push the entire discussion to the back of their minds. Instead, here are my suggested takeaways:

- The space of possible minds is much vaster than the set of minds that already exist here on earth

- If we succeed in creating an ASI, it may have characteristics that are radically different from human intelligence

- The ethical principles that appeal to an ASI may be radically different to the ones that appeal to you and me

- An ASI may soon lose interest in human wellbeing; or it may become tied to the interests of a small rogue group of humans who care little for the majority of the human population

- Until such time as we have good reasons for confidence that we know how to create an ASI that will have an inviolable commitment to ongoing human flourishing, we should avoid any steps that will risk an ASI passing beyond our control

- The most promising line of enquiry may involve an ASI having intelligence but no consciousness, sentience, autonomy, or independent volition.

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)