Going nowhere fast

Imagine you’re listening to someone you don’t know very well. Perhaps you’ve never even met in real life. You’re just passing acquaintances on a social networking site. A friend of a friend, say. Let’s call that person FoF.

FoF is making an unusual argument. You’ve not thought much about it before. To you, it seems a bit subversive.

You pause. You click on FoF’s profile, and look at other things he has said. Wow, one of his other statements marks him out as an apparent supporter of Cause Z. (That’s a cause I’ve made up for the sake of this fictitious dialog.)

You shudder. People who support Cause Z have got their priorities all wrong. They’re committed to an outdated ideology. Or they fail to understand free market dynamics. Or they’re ignorant of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Whatever. There’s no need for you to listen to them.

Indeed, since FoF is a supporter of Cause Z, you’re tempted to block him. Why let his subversive ill-informed ideas clutter up your tidy filter bubble?

But today, you’re feeling magnanimous. You decide to break into the conversation, with your own explanation of why Cause Z is mistaken.

In turn, FoF finds your remarks unusual. First, it’s nothing to do with what he had just been saying. Second, it’s not a line of discussion he has heard before. To him, it seems a bit subversive.

FoF pauses. He clicks on your social media profile, and looks at other things you’ve said. Wow. One of your other statements marks you out as an apparent supporter of Clause Y.

FoF shudders. People who support Cause Y have got their priorities all wrong.

FoF feels magnanimous too. He breaks into your conversation, with his explanation as to why Cause Y is bunk.

By now, you’re exasperated. FoF has completely missed the point you were making. This time you really are going to block him. Goodbye.

The result: nothing learned at all.

And two people have had their emotions stirred up in unproductive ways. Goodness knows when and where each might vent their furies.

Trying again

We’ve all been the characters in this story on occasion. We’ve all missed opportunities to learn, and, in the process, we’ve had our emotions stirred up for no good reason.

Let’s consider how things could have gone better.

The first step forward is a commitment to resist prejudice. Maybe FoF really is a supporter of Cause Z. But that shouldn’t prejudge the value of anything else he also happens to say. Maybe you really are a supporter of Cause Y. But that doesn’t mean FoF should jump to conclusions about other opinions you offer.

Ideally, ideas should be separated from the broader philosophies in which they might be located. Ideas should be assessed on their own merits, without regard to who first advanced them – and regardless of who else supports them.

In other words, activists must be ready to set aside some of their haste and self-confidence, and instead adopt, at least for a while, the methods of the academy rather than the methods of activism.

That’s because, frankly, the challenges we’re facing as a global civilization are so complex as to defy being fully described by any one of our worldviews.

Cause Z may indeed have useful insights – but also some nasty blindspots. Likewise for Cause Y, and all the other causes and worldviews that gather supporters from time to time. None of them have all the answers.

On a good day, FoF appreciates that point. So do you. Both of you are willing, in principle, to supplement your own activism with a willingness to assess new ideas.

That’s in principle. The practice is often different.

That’s not just because we are tribal beings – having inherited tribal instincts from our prehistoric evolutionary ancestors.

It’s also because the ideas that are put forward as starting points for meaningful open discussions all too often fail in that purpose. They’re intended to help us set aside, for a while, our usual worldviews. But all too often, they have just a thin separation from well-known ideological positions.

These ideas aren’t sufficiently interesting in their own right. They’re too obviously a proxy for an underlying cause.

That’s why real effort needs to be put into designing what can be called transcendent questions.

These questions are potential starting points for meaningful non-tribal open discussions. These questions have the ability to trigger a suspension of ideology.

But without good transcendent questions, the conversation will quickly cascade back down to its previous state of logjam. That’s despite the good intentions people tried to keep in mind. And we’ll be blocking each other – if not literally, then mentally.

The AI conversation logjam

Within discussions of the future of AI, some tribal positions are well known –

One tribal group is defined by the opinion that so-called AI systems are not ‘true’ intelligence. In this view, these AI systems are just narrow tools, mindless number crunchers, statistical extrapolations, or stochastic parrots. People in this group delight in pointing out instances where AI systems make grotesque errors.

A second tribal group is overwhelmed with a sense of dread. In this view, AI is on the point of running beyond control. Indeed, Big Tech is on the point of running beyond control. Open-source mavericks are on the point of running beyond control. And there’s little that can be done about any of this.

A third group is focused on the remarkable benefits that advanced AI systems can deliver. Not only can such AI systems solve problems of climate change, poverty and malnutrition, cancer and dementia, and even aging. Crucially, they can also solve any problems that earlier, weaker generations of AI might be on the point of causing. In this view, it’s important to accelerate as fast as possible into that new world.

Crudely, these are the skeptics, the doomers, and the accelerationists. Sadly, they often have dim opinions of each other. When they identify a conversation partner as being a member of an opposed tribe, they shudder.

Can we find some transcendent questions, which will allow people with sympathies for these various groups to overcome, for a while, their tribal loyalties, in search of a better understanding? Which questions might unblock the AI safety conversation logjam?

A different starting point

In this context, I want to applaud Rob Bensinger. Rob is the communications lead at an organization called MIRI (the Machine Intelligence Research Institute).

(Just in case you’re tempted to strop away now, muttering unkind thoughts about MIRI, let me remind you of the commitment you made, a few paragraphs back, not to prejudge an idea just because the person raising it has some associations you disdain.)

(You did make that commitment, didn’t you?)

Rob has noticed the same kind of logjam and tribalism that I’ve just been talking about. As he puts it in a recent article:

Recent discussions of AI x-risk in places like Twitter tend to focus on “are you in the Rightthink Tribe, or the Wrongthink Tribe?” Are you a doomer? An accelerationist? An EA? A techno-optimist?

I’m pretty sure these discussions would go way better if the discussion looked less like that. More concrete claims, details, and probabilities; fewer vague slogans and vague expressions of certainty.

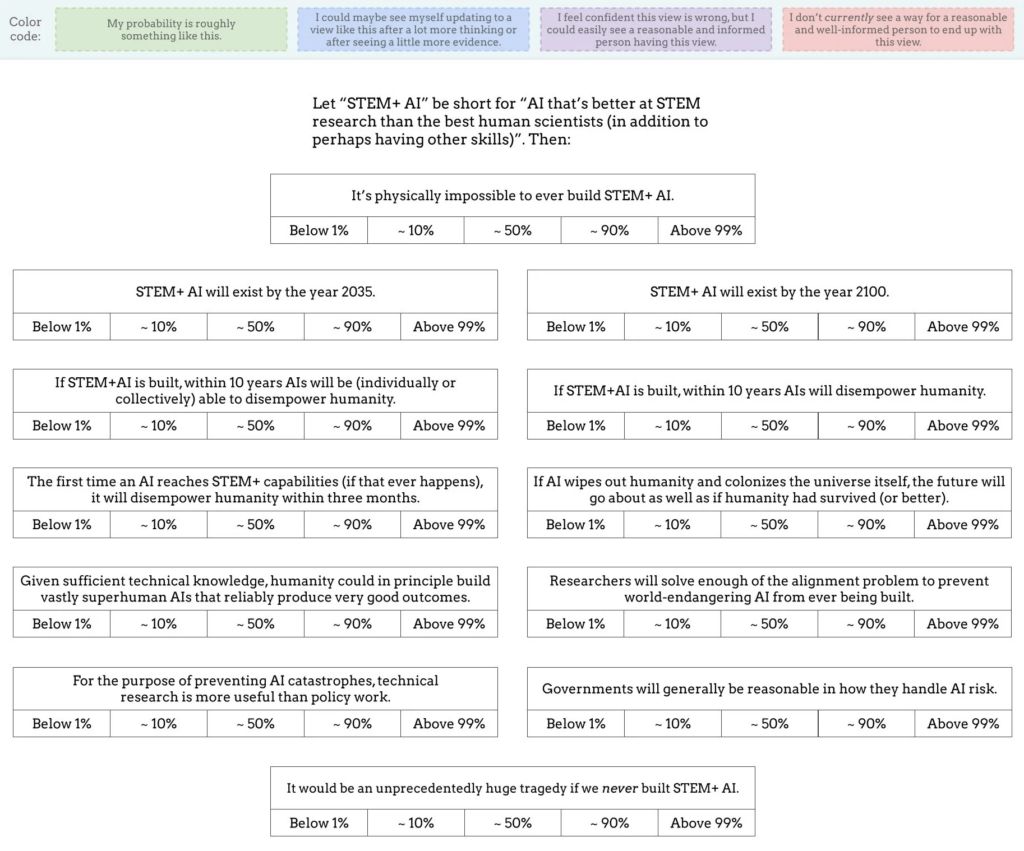

Following that introduction, Rob introduces his own set of twelve questions, as shown in the following picture:

For each of the twelve questions, readers are invited, not just to give a forthright ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer, but to think probabilistically. They’re also invited to consider which range of probabilities other well-informed people with good reasoning abilities might plausibly assign to each answer.

It’s where Rob’s questions start that I find most interesting.

PCAI, SEMTAI, and PHUAI

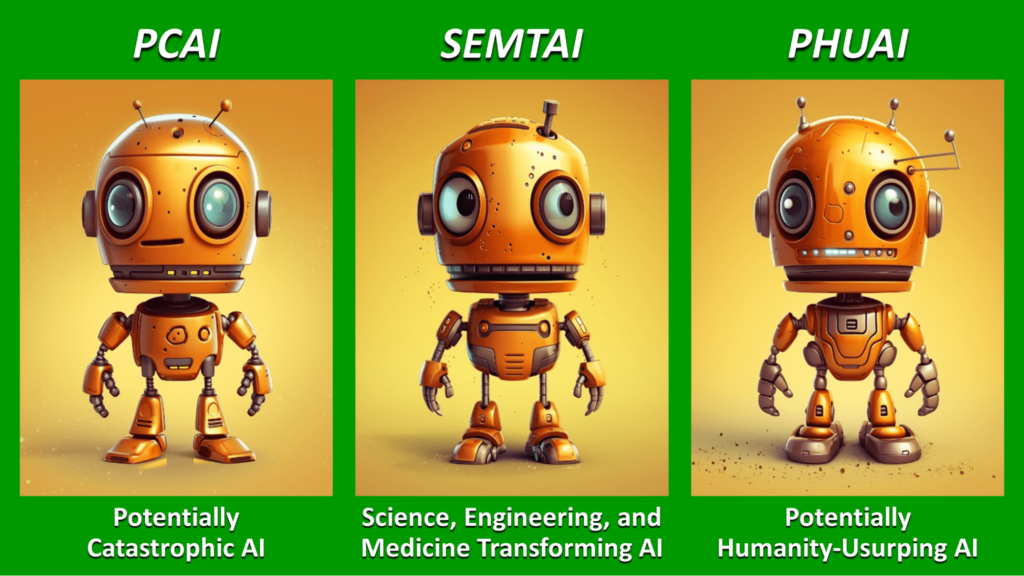

All too often, discussions about the safety of future AI systems fail at the first hurdle. As soon as the phrase ‘AGI’ is mentioned, unhelpful philosophical debates break out.That’s why I have been suggesting new terms, such as PCAI, SEMTAI, and PHUAI:

I’ve suggested the pronunciations ‘pea sigh’, ‘sem tie’, and ‘foo eye’ – so that they all rhyme with each other and, also, with ‘AGI’. The three acronyms stand for:

- Potentially Catastrophic AI

- Science, Engineering, and Medicine Transforming AI

- Potentially Humanity-Usurping AI.

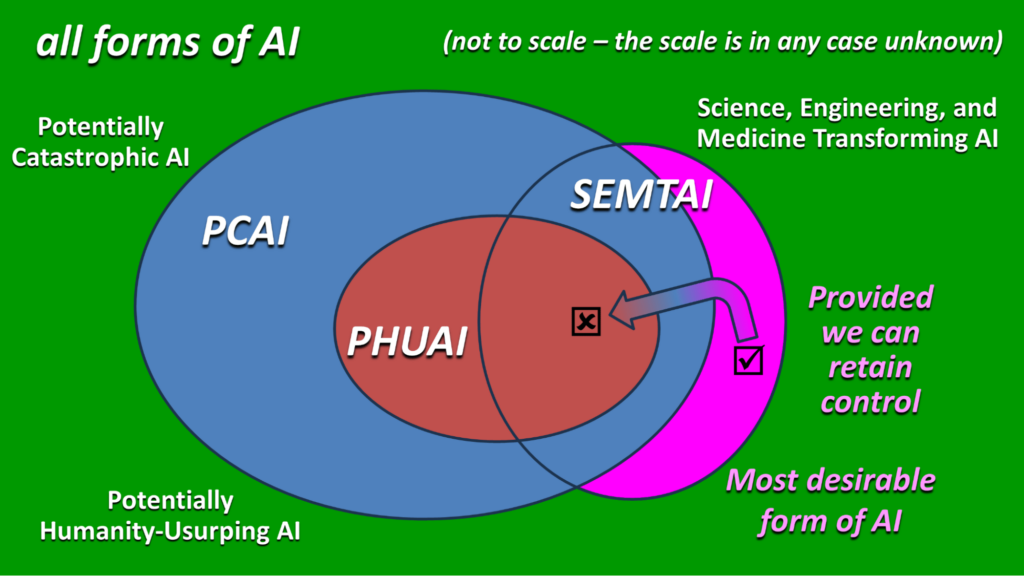

These concepts lead the conversation fairly quickly to three pairs of potentially transcendent questions:

- “When is PCAI likely to be created?” and “How could we stop these potentially catastrophic AI systems from being actually catastrophic?”

- “When is SEMTAI likely to be created?” and “How can we accelerate the advent of SEMTAI without also accelerating the advent of dangerous versions of PCAI or PHUAI?”

- “When is PHUAI likely to be created?” and “How could we stop such an AI from actually usurping humanity into a very unhappy state?”

The future most of us can agree as being profoundly desirable, surely, is one in which SEMTAI exists and is working wonders, uplifting the disciplines of science, engineering, and medicine.

If we can gain these benefits without the AI systems being “fully general” or “all-round superintelligent” or “independently autonomous, with desires and goals of its own”, I would personally see that as an advantage.

But regardless of whether SEMTAI actually meets the criteria various people have included in their own definitions of AGI, what path gives humanity SEMTAI without also giving us PCAI or even PHUAI? This is the key challenge.

Introducing ‘STEM+ AI’

Well, I confess that Rob Bensinger didn’t start his list of potentially transcendent questions with the concept of SEMTAI.

However, the term he did introduce was, as it happens, a slight rearrangement of the same letters: ‘STEM+ AI’. And the definition is pretty similar too:

Let ‘STEM+ AI’ be short for “AI that’s better at STEM research than the best human scientists (in addition to perhaps having other skills).

That leads to the first three questions on Rob’s list:

- What’s the probability that it’s physically impossible to ever build STEM+ AI?

- What’s the probability that STEM+ AI will exist by the year 2035?

- What’s the probability that STEM+ AI will exist by the year 2100?

At this point, you should probably pause, and determine your own answers. You don’t need to be precise. Just choose between one of the following probability ranges:

- Below 1%

- Around 10%

- Around 50%

- Around 90%

- Above 99%

I won’t tell you my answers. Nor Rob’s, though you can find them online easily enough from links in his main article. It’s better if you reach your own answers first.

And recall the wider idea: don’t just decide your own answers. Also consider which probability ranges someone else might assign, assuming they are well-informed and competent in reasoning.

Then when you compare your answers with those of a colleague, friend, or online acquaintance, and discover surprising differences, the next step, of course, is to explore why each of you have reached your conclusions.

The probability of disempowering humanity

The next question that causes conversations about AI safety to stumble: what scales of risks should we look at? Should we focus our concern on so-called ‘existential risk’? What about ‘catastrophic risk’?

Rob seeks to transcend that logjam too. He raises questions about the probability that a STEM+ AI will disempower humanity. Here are questions 4 to 6 on his list:

- What’s the probability that, if STEM+AI is built, then AIs will be (individually or collectively) able, within ten years, to disempower humanity?

- What’s the probability that, if STEM+AI is built, then AIs will disempower humanity within ten years?

- What’s the probability that, if STEM+AI is built, then AIs will disempower humanity within three months?

Question 4 is about capability: given STEM+ AI abilities, will AI systems be capable, as a consequence, to disempower humanity?

Questions 5 and 6 move from capability to proclivity. Will these AI systems actually exercise these abilities they have acquired? And if so, potentially how quickly?

Separating the ability and proclivity questions is an inspired idea. Again, I invite you to consider your answers.

Two moral evaluations

Question 7 introduces another angle, namely that of moral evaluation:

- 7. What’s the probability that, if AI wipes out humanity and colonizes the universe itself, the future will go about as well as if humanity had survived (or better)?

The last question in the set – question 12 – also asks for a moral evaluation:

- 12. How strongly do you agree with the statement that it would be an unprecedentedly huge tragedy if we never built STEM+ AI?

Yet again, these questions have the ability to inspire fruitful conversation and provoke new insights.

Better technology or better governance?

You may have noticed I skipped numbers 8-11. These four questions may be the most important on the entire list. They address questions of technological possibility and governance possibility. Here’s question 11:

- 11. What’s the probability that governments will generally be reasonable in how they handle AI risk?

And here’s question 10:

- 10. What’s the probability that, for the purpose of preventing AI catastrophes, technical research is more useful than policy work?

As for questions 8 and 9, well, I’ll leave you to discover these by yourself. And I encourage you to become involved in the online conversation that these questions have catalyzed.

Finally, if you think you have a better transcendent question to drop into the conversation, please let me know!

Let us know your thoughts! Sign up for a Mindplex account now, join our Telegram, or follow us on Twitter.

.png)

.png)

.png)